Rate this article and enter to win

Ever think about what you would do if you were caught up in an active shooting scenario? For anyone paying attention to the national news, it’s hard not to go there mentally. In a recent study by Student Health 101, over two-thirds of students at US colleges said they think seriously about what could happen and what they would do if they encountered an active shooter.

Other threats are far more likely

Active shootings in colleges and other public locations generate horrifying media coverage. But most experts on gun violence agree that campus shootings are still relatively rare—campus deaths are far more likely to be caused by traffic accidents, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Among the things that one could learn to protect themselves from, I would put mass shootings far down the list of risks faced by students,” says Dr. Deborah Azrael, director of research at the Harvard Injury Control Research Center in Massachusetts. “You want to learn CPR, what to do in a fire, but the likelihood that someone is faced with an active shooter is slim.”

But active shootings are increasing

Data on gun violence in schools is hard to track—some organizations look only at active shooter scenarios, while others count any incident involving a gun that might occur on school property—but most estimates indicate it is increasing. One study conducted by the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City found that gun violence on college campuses in the US jumped from just 12 incidents in the 2010–2011 school year to 30 shootings in the 2015–2016 school year.

“If you look historically, over time, we’re seeing increases in the incidence of shootings at schools, particularly at the college and university level,” says Dr. Amy Thompson, professor of public health at the University of Toledo in Ohio. Mass killings and school shootings may be contagious, research suggests, with high-profile incidents and media coverage inspiring additional attacks (PLOS ONE, 2015).

In 2016 and 2017, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counted 50 active shootings in the US (20 in 2016 and 30 in 2017). Only seven of these incidents occurred in an educational setting. However, that’s an increase from the 40 incidents that happened in 2014–2015.

How to be prepared for an active shooting event

In general, planning for emergency scenarios is thought to increase our chances of survival because it may help us overcome the freeze response that can prevent us from taking quick action in emergencies. “There’s really no way to know what is the best approach in [an active shooting event], but it’s absolutely worth thinking about,” says Dr. Thompson.

In dangerous situations, most people freeze initially, wrote Dr. Joseph Ledoux, director of the Emotional Brain Institute at New York University, in the New York Times in 2015. Learning to “reappraise” that freeze instinct may help us shift into action mode. “Even if this cut only a few seconds off our freezing, it might be the difference between life and death,” he wrote.

Here’s where to start:

- Get into the habit of looking for exit signs and outside-facing windows in every public place you attend.

- Stay aware of your surroundings.

- If active shootings are on your mind, check out the Run-Hide-Fight protocol below. While this protocol is no guarantee, it could be helpful.

What to do in the moment

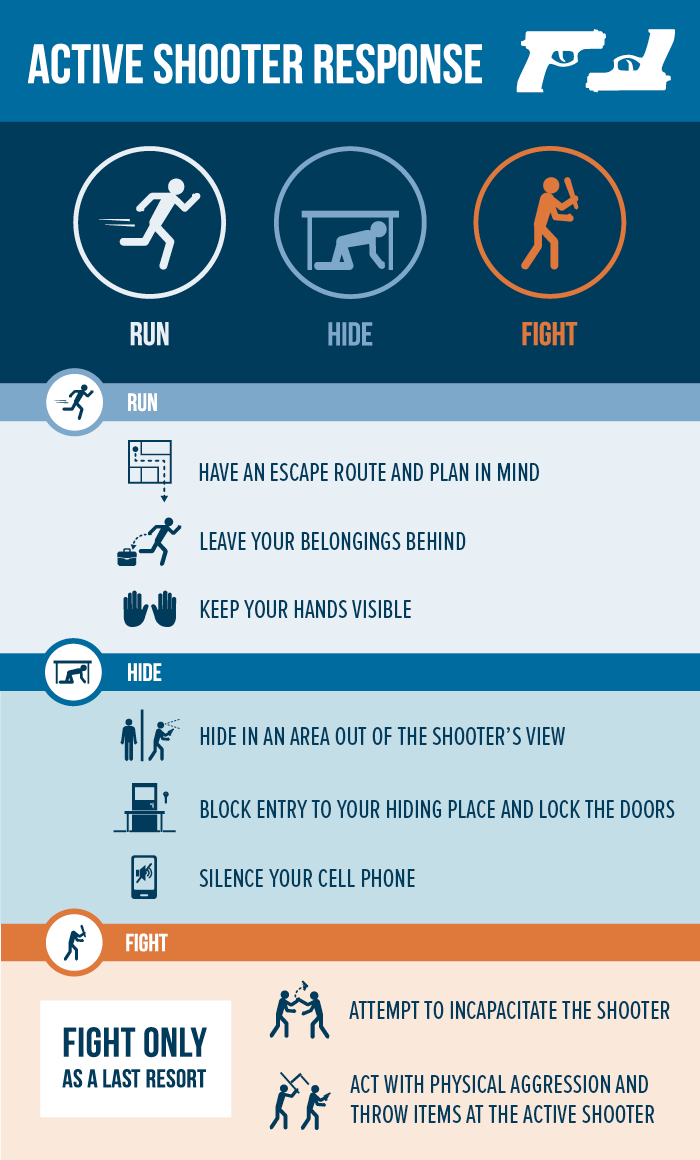

Run-Hide-Fight

This response was developed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the FBI.

Run

- Have an escape route and plan in mind

- Leave your belongings behind

- Keep your hands visible

Hide

- Hide in an area out of the shooter’s view

- Block entry to your hiding place and lock the doors

- Silence your cell phone

Fight

- Fight only as a last resort

- Attempt to incapacitate the shooter

- Act with physical aggression and throw items at the active shooter

Leaving the scene, run with your hands up so police officials can identify you quickly and not mistake you for the shooter, the FBI recommends.

There’s no bulletproof response

Evaluating any active shooter protocol is difficult. Relatively few people have been involved in active shooting events. Of those who have, it’s difficult or impossible to know whether their specific response was the reason for their survival. And in an unpredictable emergency situation, no method covers all possibilities. We may not be able to predict, for example, the implications of running out of a building. That said, researchers have speculated that the will to live is an important part of a survivor mentality.

Prevent a shooting before it happens

Your best defense as a student is to be aware of your friends and classmates who might be showing signs of pending violence and help connect them with relevant resources. “This approach would be a better investment [for preventing] all sorts of violence than spending a lot of time figuring out what one would do in the unlikely event that someone showed up in a classroom with a gun,” says Dr. Azrael.

Mass shooters tend to fit a standard profile, but it’s broad. “If you told me there was a mass shooting and asked me who had done it, I would be able to give you a pretty good guess: a man between the ages of 18 and 29 who was somewhat isolated or who had some constellation of issues that were diagnosed or not,” say Dr. Azrael. On the other hand, she says, “I wouldn’t be able to tell you who among that big group of people might be a shooter.”

Sometimes, however, the shooter tells us in advance. “In most cases of school shootings, the person told someone else that they were going to do it,” says Dr. Thompson. “Always take such threats seriously and act quickly. Time is of the essence.”

If you witness certain behaviors in another student, immediately contact the dean of students, the counseling center, another staff or faculty member, or campus security. Campus officials may be able to further assess the individual and/or the situation to help determine what type of intervention is warranted. Never try to defuse these types of individuals and/or situations on your own. Often, these professionals can preserve your anonymity. The following behaviors are red flags that merit assessment or intervention, especially if they seem out of character in the person concerned:

- Continuous or excessive anger issues

- Becoming easily agitated

- Revealing a preoccupation with violence or death

- Suddenly distancing themselves from others or becoming withdrawn

- Collecting large amounts of firearms

- Talking about suicide, especially killing others and then hurting themselves

Guide for citizens caught in an active shooting: US Department of Homeland Security

Safety guide for campus shootings: Northwestern University

Staying Alive video series: Safe Havens International

Custom data on campus safety: US Department of Education

Article sources

Deborah Azrael, PhD, director of research, Harvard Injury Control Research Center, Massachusetts.

Amy Thompson, PhD, professor of public health, University of Toledo, Ohio.

Albrecht, S. (2014, August 25). The truth behind the Run-Hide-Fight debate. PsychologyToday.com. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-act-violence/201408/the-truth-behind-the-run-hide-fight-debate

Arrigo, B. A., & Acheson, A. (2016). Concealed carry bans and the American college campus: A law, social sciences, and policy perspective. Contemporary Justice Review, 19(1), 120–141.

Cannon, A. (2016, October). Aiming at students: The college gun violence epidemic. Citizens of Crime Commission of New York City. Retrieved from http://www.nycrimecommission.org/pdfs/CCC-Aiming-At-Students-College-Shootings-Oct2016.pdf

Dahl, P. P., Bonham, G., & Reddington, F. P. (2016). Community college faculty: Attitudes toward guns on campus. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40, 706–717.

Dorn, M., & Slattery, S. (2012). Fight, flight, or lockdown: Teaching students and staff to attack active shooters could result in decreased casualties or needless deaths. CampusSafetyMagazine.com. Retrieved from http://www.campussafetymagazine.com/files/resources/Fight-Flight-or-Lockdown.pdf

Ellifritzm, G. (2012, December 12). New “rapid mass murder” research from Ron Borsch. Activeresponsetraining.com. Retrieved from http://www.activeresponsetraining.net/new-rapid-mass-murder-research-from-ron-borsch

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2013, September 16). A study of active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf/view

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2018, April). Active shooter incidents in the United States in 2016 and 2017. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-us-2016-2017.pdf/view

Hemenway, D., & Solnick, S. J. (2015). The epidemiology of self-defense gun use: Evidence from the National Crime Victimization Surveys 2007–2011. Preventive Medicine, 79, 22–27.

Ledoux, J. (2015, December 18). “Run, Hide, Fight” is not how our brains work. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/20/opinion/sunday/run-hide-fight-is-not-how-our-brains-work.html?_r=0

Muschert, G. W. (2007). Research in school shootings. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 60–80.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2018, March). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2017. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018036.pdf

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). School shooting resources. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/terrorism-and-violence/school-shooting-resources

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2016, May 5). Guns on campus overview. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/guns-on-campus-overview.aspx

Ordway, D. M. (2016, September 22). Campus carry and the concealed carry of guns on college campuses: A collection of research. JournalistsResource.org. Retrieved from http://journalistsresource.org/studies/society/education/concealed-carry-guns-college-campus-research

Price, J. H., Thompson, A., Khubchandani, J., Dake, J., et al. (2014). University presidents’ perceptions and practice regarding the carrying of concealed handguns on college campuses. Journal of American College Health, 62(7), 461–469.

SafeColleges. (n.d.). Active shooter. Retrieved from https://www.safecolleges.com/hot-topics/active-shooter-topic/

Siebert, A. (2001). The survivor personality. New York: Putnam.

Student Health 101 survey, February 2019.

Students for Concealed Carry. (2009). Crime on college campuses in the US. Retrieved from http://concealedcampus.org/campus-crime/

Thompson, A., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., Teeple, K., et al. (2013). Student perceptions and practices regarding carrying concealed handguns on university campuses. Journal of American College Health, 61(5), 243–253.

Towers, S., Gomez-Lievano, A., Khan, M., Mubayi, A., et al. (2015). Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLOS ONE. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117259

Turner, J. C., Leno, E. V., & Keller, A. (2013). Causes of mortality among American college students: A pilot study. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 27(1), 31–42. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2013.739022

Webster, D. W., Donohue, J. J., Klarevas, L., Crifasi, C. K., et al. (2016, October 16). Firearms on college campus: Research evidence and policy implications. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/_pdfs/GunsOnCampus.pdf