How to know when to “break up” with a toxic friend

Reading Time: 7 minutes Toxic friendships can really take their toll. Here’s how to handle them.

Reading Time: 7 minutes Toxic friendships can really take their toll. Here’s how to handle them.

Reading Time: 8 minutes What to do if a friend becomes too much.

Reading Time: 9 minutes Scientists are finding that our gut microbiome affects our brain and mental health more than we knew.

Reading Time: 12 minutes As a society, we are more socially isolated than ever. Learn why building a social support system is the missing piece in your self-care puzzle.

Rate this article and enter to win

Deliberately hurting oneself is among those human behaviors that seem baffling and counter-intuitive from the outside. A student who parties, gets depressed, and ends up cutting himself may fear that his peers just wouldn’t get it. A student who realizes that a friend pulls out her own hair may have no idea how to help. While most college students do not deliberately harm or injure themselves, it’s certainly happening on campuses, studies show.

“Self-injury tends to go through jags,” says Dr. Janis Whitlock, director of the Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery at Cornell University, New York. “It’s not uncommon for someone to not injure for a year and then start again in college when they get triggered by a variety of stressors—everything from academic to romantic problems.” Understanding self-injury can help clue us in to the complexities of our own and others’ experience, and lead us to healthy ways to handle the stresses of school, however they manifest.

When people intentionally cause harm, pain, or damage to their own body, without the intent to die, it’s called non-suicidal self-injury (or self-harm). We tend to think of self-injury as cutting. In reality, it can be any type of behavior that intentionally causes tissue damage to the body, so it could involve burning, pulling out hair, or some acts of externalized aggression, such as punching walls. Self-injury may happen under the influence of drugs or alcohol (though using alcohol or drugs is not itself considered self-injury). Self-injury is different from suicidal self-harm, which is motivated by the intent to die and includes suicidal thinking. That said, people who self-injure are more likely than others to consider suicide (see: What raises the risk for self-injury?).

Self-injury can happen as a result of not being able to cope with certain stressors or emotions. “The behavior is seen a lot in college because the pressures during this timeframe—like grades, relationships, and jobs—increase,” says Dr. Retta Evans, associate professor of Community Health and Human Services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Self-injury is more common in young adults who are also experiencing depression or anxiety, sexual abuse or trauma, eating disorders, or substance abuse. People who are LGBTQ are also at relatively high risk, perhaps because of the stress of social judgment. “Self-injury was a way to release inner pain that I didn’t know how to talk about,” says a third-year undergraduate at St. Clair College, Ontario.

People self-injure for a variety of reasons. Sometimes those reasons evolve over time. In our survey, many students referred to self-injury as a temporary behavior that they had managed to move past. “When I was in foster care I began to self-injure. I had recently been removed from a very dangerous situation and was dealing with what I had survived. I stopped harming myself when I was ready; I meditated a lot and worked through my issues,” said a fourth-year undergraduate at Portland State University, Oregon.

These are among the most common reasons for self-injuring:

1 To experience emotions differently

“I have severe anxiety attacks. Self-injury is a form of manifesting the emotional pain into physical pain. By doing this, I tell myself my pain is real.”

—Second-year undergraduate, Portland State University, Oregon

2 To “take away” or escape from unwanted feelings or thoughts

“Self-injury to me meant an escape from emotional pain that I did not understand and did not want my family to see. It happened because I did not want to be seen as weak in my family’s eyes; I was supposed to be a role model.”

—Fourth-year undergraduate, Dominican University, California

3 To bring recognition to their problems

“For me, it was a cry for attention. I was not getting the help I needed and had no real coping mechanisms.”

—First-year undergraduate, East Tennessee State University

4 To avoid taking anger out on someone else

“I got so angry that I hurt myself because I couldn’t hurt the other person. I am a nice person, but when people do mean things toward me, I hurt myself instead. It’s the only way I can vent.”

—Fourth-year graduate student, Berea College, Kentucky

5 To punish yourself or help you deal with a failure

“For me, self-injury was my way of punishing myself for who I was. I hated myself for things I did and the way I was. I hated who I was and thought I didn’t deserve happiness.”

—Fourth-year undergraduate, California State University, Stanislaus

6 To continue the habit

“Self-injury was a form of punishing myself for perceived ‘stupidity’ when it began. But it’s currently a compulsion when I experience severe frustration or stress.”

—Second-year graduate student, University of Rhode Island

Most people who self-injure start as teens—but self-injury is not a problem that goes away when they graduate high school. It can continue into college, restart when pressure builds, or begin later, experts say. “It’s very episodic, for a lot a people,” says Dr. Janis Whitlock, director of the Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery at Cornell University, New York.

People don’t talk much about self-injuring, so it’s hard to know how commonly it happens. In a 2011 study, 15 percent of college students said they had self-injured at some point, and 7 percent had in the past year (Journal of American College Health), though estimates vary. In surveys, more women tend to report self-injury than men. On campuses, however, women and men may self-injure at similar rates. Most people who self-injure don’t seek support, research shows.

What raises the risk for self-injury?

1 Age

2 Depression and anxiety

3 Child abuse and trauma

4 Eating disorders

5 Substance abuse

6 Minority sexual or gender identity

Research is currently mixed on this issue. Girls and women seem to self-injure more commonly than boys and men do. But some studies suggest that during young adulthood, men and women may self-injure at similar rates. For example, the 2011 study of college students found that women were more likely than men to report that they had ever self-injured, but women and men were equally likely to say they had self-injured within the past year (Journal of American College Health). (The student comments in this article come from men and women.)

Researchers have two main theories that may help explain the perceived gender differences in self-injury:

“In some ways, men are better at hiding it than women [perhaps due to traditional gender roles]. If we see wounds on a guy’s knuckles we [might] assume he’s been working on a car or in a fight,” says Dr. Whitlock. “To an outsider, it looks like they’re trying to cause someone else pain, but the underlying motivation is often to cause themselves pain. For women, the telltale cuts on arms or ankles might be more obvious.”

Student voices

“My self-injury involved punching walls and seeking out fights to vent anger and frustration. Usually under the influence of alcohol.”

—Fifth-year undergraduate (male), University of New Brunswick

“For many years I cut my thighs. They are horribly scarred now. I chose my thighs because I was embarrassed and didn’t want it to be obvious. I did it to cope and calm down because it always cleared my head. I was in a dark place, but I hid it from my friends and family

—just like the scars.” —Fourth-year undergraduate (female), University of New Brunswick

Usually, when people learn how to cope with their emotions and talk about how they feel, they experience less of an urge to hurt themselves. Simple techniques and skills can decrease the intensity of emotions and make them more manageable. “Finding a different outlet [for distress] was the key to my recovery,” says a second-year undergraduate at SAIT Polytechnic, Alberta. These three approaches can help you or a friend:

1 Reach out and talk

If you are self-injuring, reach out. Talk to a friend, mentor, RA, professor, member of your religious community, or member of your support group (in person or online). Ask for their support, and spend time with people who make you feel good.

If you’re concerned that someone else may be self-injuring, check in with them. “Let your friend know you care,” says Dr. Lance Swenson, associate professor in psychology at Suffolk University, Massachusetts. “Remind your friend you are there to listen. Tell them you can help them get help. Most people who self-injure are not consciously aware of why they are [doing it], at least not in the moment.” Seek out support for yourself too, so that you’re in a strong position to be there for your friend.

“Let your friend know you care,” says Dr. Lance Swenson, an associate professor in the psychology department at Suffolk University, Massachusetts. “Remind your friend you are there to listen. Tell them you can help them get help. Most people who self-injure are not consciously aware of why they are [doing it], at least not in the moment. They shouldn’t feel like they have to face it alone.”

That said, it’s not on you to solve this. “The roots of self-injurious behavior are likely very complicated. No matter how much you care about a friend, and how hard you try to help, they may continue this behavior despite your best efforts to help them,” says Dr. Davis Smith, a physician at the University of Connecticut.

How to talk to a friend you are concerned about:

2 Test coping strategies and figure out what works

If you’re concerned about a friend, you may be able to help them explore these techniques. If you’re self-injuring, test these strategies and take note of what helps. “Distress tolerance skills” can be used in place of self-injury. See Get help or find out more (below) for more info.

1 Do the opposite of what you feel:

For example, listen to your favorite upbeat song, or watch a funny YouTube video. Look in the mirror and smile—watch as your expression changes.

2 Exercise hard and fast:

Do 25 jumping jacks, go for a jog, or dance around the room. Research shows that cardio exercise can reduce your stress and improve your mood. Regular physical activity can be protective.

3 Use your five senses:

This helps you connect with what is going on around you and anchor yourself in the present moment. For example, sink your heels into the floor or ground and focus on how it feels beneath your body. Hold something soft or fuzzy. Squeeze a stress ball. Place a cool, wet washcloth on your face. Light a scented candle and breathe in deeply. Cook and/or eat your favorite food and really allow yourself to enjoy the flavor. Go for a walk or drive and take in the sights and smells. Take ice from the freezer and hold it tightly in your hand. Get into warm water (take a shower or bath).

4 Take slow, deep breaths:

Imagine you are blowing up a balloon. When you inhale deeply, your lower belly should expand. Count to three on each inhale and each exhale.

5 Think about your emotions:

Face them instead of pushing them away. Labeling an emotion (e.g., “My heart is racing and I’m feeling anxious”) can often help you figure out why you’re feeling that way (e.g., “I have a big exam coming up next week and I’m anxious about studying for it”). Write down how you’re feeling in a notebook or journal.

6 Focus on your heart:

Put your hand on your heart so you can feel your heartbeat and count the beats per minute. Try to slow down your heart rate by taking slow, deep breaths.

7 Actively cherish what you have:

Look at pictures on your phone or computer that make you smile. Make a list of all of the things you are grateful for or happy about in your life.

8 Actively cherish who you are:

Make a list of your accomplishments—e.g., “I do pretty well in school,” “I am a caring friend,” “I take excellent care of my dog.”

9 Sink into something else:

Read a book, story, or article. Listen to your favorite music, play an instrument, or sing (even if you have no musical talent!). Engage in your favorite hobby or master a skill, such as gardening, cooking, baking, playing a video game, knitting, painting, or drawing.

10 Prioritize sleep:

Get up as close to the same time every day as possible; this will help you go to bed at a more regular time too. Your bed is for sleeping only (no electronics or social networking). Relish it.

3 Consider seeking professional support

Checking in with a counselor can relieve some of the pressure and help you find strategies and resources you wouldn’t otherwise know about—whether it’s you who’s self-injuring or your friend. Your student health center or counseling center may be able to help directly or refer you to an expert medical provider. Certain therapeutic techniques—such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavioral therapy—are designed to build healthy coping skills directly. If you ever feel suicidal, call 911, go to the nearest emergency room, or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

“I did not want to feel hopeless and alone anymore,” says a first-year undergraduate at California State University, Channel Islands. “I decided go to counseling to cope with my self-injuring tendencies. Every session I attended helped me gain the confidence to be myself, and most importantly, to love myself. Don’t be afraid to seek help.”

Find out here Fourth-year undergraduate, Portland State University, Oregon “Resisting the urge to self-injure as a coping mechanism can be a constant struggle for many. Calm Harm is designed to manage that urge and direct users to safer and more effective ways of managing stressors.” USEFUL? FUN? EFFECTIVE?

![]()

Based on dialectical behavioral therapy (worth looking into on its own), the app provides options for what you can do instead of hurting yourself when you’re feeling negative emotions. While clicking through menus is tedious at times, the techniques were actually helpful (which was my main concern).

![]()

Helpful and appropriate, definitely. But something like this isn’t really ever going to be “fun”—the question is whether it works.

![]()

No app will “solve” the problem outright, but this has real potential to help. Calm Harm does what it sets out to do: provide alternatives to self-harm in the short term so that more definitive treatment can be sought/have time to work.

Comprehensive guide to self-injury and recovery: Cornell University

Overview and resources on self-harm: National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Brief guide to distress tolerance skills: TherapistAid

Overview of distress tolerance skills [slideshow]: University of Washington

Understanding self-injury [infographic]: Cornell University

Treatment info and resources: SAFE Alternatives

Support for LGBTQ emotional health: National Alliance on Mental Illness

[survey_plugin]

Article sourcesRetta R. Evans, PhD, MCHES, associate professor, program coordinator, Community Health & Human Services, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Michelle M. Seliner, MSW, LCSW, chief operating officer, S.A.F.E. Alternatives.

Lance P. Swenson, PhD, associate professor, Suffolk University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Janis Whitlock, PhD., director, Cornell Research Center on Self-Injury and Recovery, Cornell University, New York.

Andover, M. S., Morris, B. W., Wren, A., & Bruzzese, M. E. (2012). The co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Distinguishing risk factors and psychosocial correlates. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 11–17. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-11

Arcelus, J., Claes, L., Witcomb, G. L., Marshall, E., et al. (2016). Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(3), 402–412.

Batejan, K. L., Jarvi, S. M., & Swenson, L. P. (2015). Relations between sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: A meta-analytic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(2), 131–150. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2014.957450

Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. (n.d.). Self-injury. Retrieved from https://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/siinfo-2.pdf

Ernhout, C., Babington, P., & Childs, M. (2015). What’s the relationship? Non-suicidal self-injury and eating disorders. The Information Brief Series, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Favazza, A. (1987). Bodies under siege: Self-mutilation in culture and psychiatry. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Heath, N. L., Toste, J. R., Nedecheva, T., & Charlebois, A. (2008). An examination of non-suicidal self-injury among college students. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30(2), 137–156.

Hoff, E. R., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury in college students: The role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 39(6), 576–587.

Jacobson, C. M., & Gould, M. (2007). The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 11, 129–147.

Jacobson, C. M., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Miller, A., & Turner, J. B. (2008). Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(2), 363–375.

Linehan, M. M. (2014). Dialectical behavioral therapy skills training manual: Second edition. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lloyd-Richardson, E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192.

Nock, M., Joiner Jr., T., Gordon, K., Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., et al. (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144(1), 65–72.

Nock, M., & Prinstein, M. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890.

Nock M., & Prinstein, M. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140–146.

Nock, M., Prinstein, M., & Sterba, S. (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 816–827.

Peebles, R., Wilson, J. L., & Lock, J. D. (2011). Self-injury in adolescents with eating disorders: Correlates and provider bias. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(3), 310–313.

Serras, A., Saules, K. K., Cranford, J. A., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Self-injury, substance use, and associated risk factors in a multi-campus probability sample of college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(1), 119–128.

Svirko, E., & Hawton, K. (2007). Self-injurious behavior and eating disorders: The extent and nature of the association. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 37(4), 409–421.

Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., et al. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303.

Sweet, M., & Whitlock, J. (2010). Therapy: Myths & misconceptions. Cornell Research Program Self-Injury and Recovery. Retrieved from https://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/therapy-myths-and-misconceptions-pm.pdf

Whitlock, J. L., & Selekman, M. (2014). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) across the lifespan. In Oxford Handbook of Suicide and Self-Injury, edited by M. Nock. Oxford Library of Psychology, Oxford University Press.

Whitlock, J. L., Muehlenkamp, J., Purington, A., Eckenrode, J., et al. (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in a college population: General trends and sex differences. Journal of American College Health, 59(8), 691–698.

Yates, T., Carlson, E., & Egeland, B. (2008). A prospective study of child maltreatment and self-injurious behavior in a community sample. Development and Psychopathology, 20(2), 651–671.

Rate this article and enter to win

Grades. Roommates. Relationships. Competition. Decisions. Obligations. Finances. College life is filled with stress generators. Stress is normal, but it can cause anxiety, and sometimes that anxiety becomes severe enough to interfere with your daily life and functioning. Left unchecked, it can lead to emotional illness, social isolation, academic failure, dropping out of school, and other unhappy outcomes.

If you—like so many students—are experiencing anxiety, you can find help. “Anxiety disorders are treatable,” says Dr. Eric Goodman, clinical psychologist at the Coastal Center for Anxiety Treatment in San Luis Obispo, California. “Often, avoiding the problem feels better in the short term. However, in the long term, you get more stuck, miss out on valued activities, and inevitably suffer more over time. Facing the problem is much scarier, and uncomfortable, but you get to reclaim your life and well-being. You become free.”

Stress is a natural and sometimes useful response to life’s demands, experts point out. “Stress in and of itself is not bad. Sometimes stress is a motivator,” says Dr. Carol Lucas, director of counseling and support services at Adelphi University, New York. For example, being a little stressed about your work may make you sit down and do it.

On the other hand, some stressors can create “mental, emotional, or physical strain,” says Dr. Lucas. We often use the words “stress” and “anxiety” interchangeably, but they describe different states of mind. Understanding that difference can help you recognize when and how to take better care of yourself.

If your stress is leading you toward unrealistic thinking, and fear of a threat that is not immediate or clear, you could use an anxiety check. That unrealistic thinking may be related to a specific situation or trigger, or it could be generalized and manifesting in various situations. See Students’ stories: Got anxiety?

Anxiety becomes a disorder when it interferes with your daily life and you can’t free yourself from the intense physical sensations or worry.

StressYour challenges exceed your resources. |

|

AnxietyYour thinking becomes less rational and somewhat catastrophic. |

|

Anxiety DisorderYour life and functioning becomes negatively affected by this “brain noise.” |

|

Generalized AnxietyYour worry persistently, excessively, and unrealistically about everyday situations and demands. |

|

Situation-specific anxiety or phobiaYou worry excessively about a particular situation or demand. |

Debbi*, third-year undergraduate, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania

(*Name changed)

“Part of the issue with anxiety is that it feels like it isn’t real, that you’re making it up. And nobody wants to report symptoms to the doctor that they’re worried aren’t even real. The nature of anxiety makes it hard to come out and say to someone, even a medical professional, ‘I don’t think that it’s normal to feel this anxious so often.’”

Debbi’s* storyBy Debbi*, third-year undergraduate, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania

(*Name changed)

What my anxiety looked and felt like

I’ve always been an anxious person. Being away from home, an only child very close to my parents, factored into it. My college schedule, with my course load and extracurriculars, was crazy; I left my room at 7:30 a.m. and got back at 10 p.m. I started waking up nauseous. I often didn’t sleep well because I was paranoid about missing my alarm. My morning routine became: wake up, cough so hard that it made me throw up, pretend that I was fine so that my roommate wouldn’t worry, and then go to class. During finals week I broke out in hives.

What happened when I went to counseling

When I eventually went to counseling services at the college, that helped. They’re free, and available to help us, so why not? You fill out a survey that rates how you’re feeling. Because it’s private, it’s easy to say, “My stress level is at a 9/10 right now,” and for the counselor to reassure you that it’s valid if that’s what you are feeling, and then to talk about why that is.

How I recognized I needed more help

In my case, counseling was not enough. My anxiety symptoms were still happening and I was just over it. This was no way to experience college. With my counselor’s blessing, I went to the doctor. I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety and seasonal affective disorder (depression in the winter months) and prescribed an antidepressant for the harder months of the year (November–May). I take long walks with my friends at night to settle my mind before bed. Being open about my feelings helps too. I’m doing much better now.

By Dr. Carol Lucas, director of counseling and support services at Adelphi University, New York

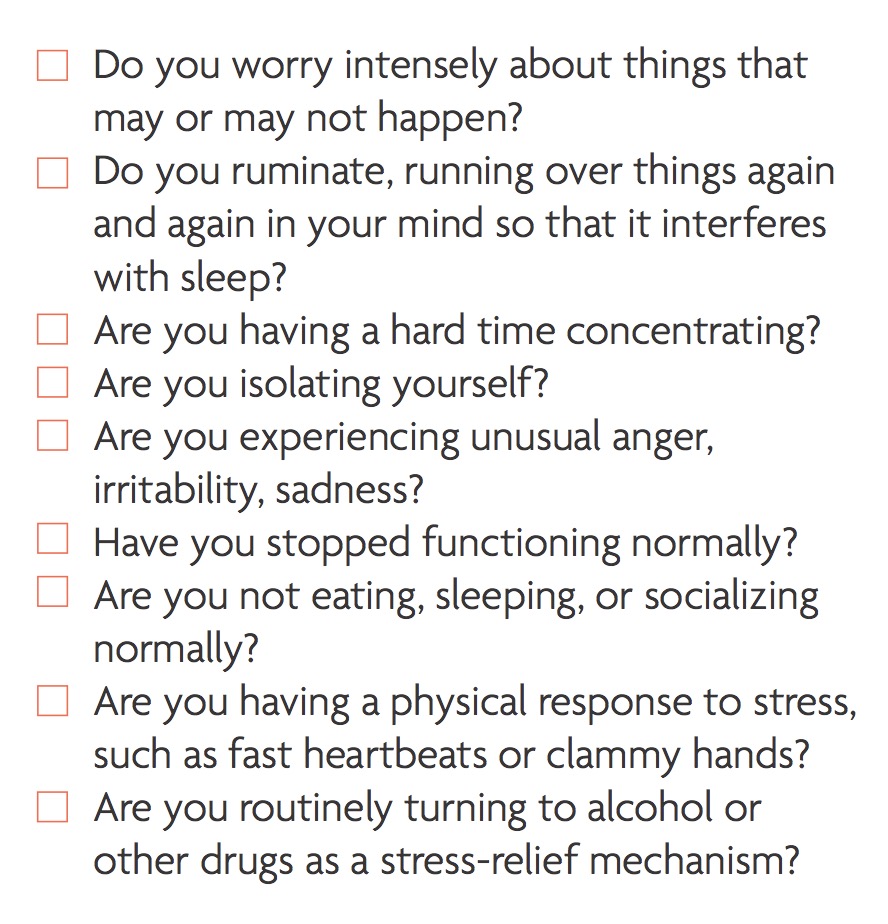

Anxious about whether or not to seek support with anxiety? Here’s how to know:

“Where young adults get into trouble in college is when they’ve missed a few assignments, maybe they’re failing, and they haven’t talked to anyone. And the further they get behind, the bigger the mountain they have to climb to get back to where they need to be,” says Dr. Laura Richardson, interim director of the division of adolescent medicine at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington.

“Ideally, we try to reach students before the stress rises to the level where it’s an anxiety disorder,” says Dr. Carol Lucas of Adelphi University, New York.

“For a lot of students, their way of coping with stress and anxiety is through rumination and intense worry and has been habituated for many, many years. Sometimes the work (in counseling) is helping them to think differently and find very effective practices to tolerate and manage anxiety and feelings,” says Dr. Lucas.

By Debbi*, third-year undergraduate, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania

(*Name changed)

Truly anxious people don’t make light of anxiety

The term “anxiety” is thrown around loosely. Everyone seems to “have anxiety;” it has almost become a trend. Everyone gets nervous and stressed out sometimes, but having an anxiety disorder is different. I’ve seen shirts around that say, “Stressed, depressed, but well dressed,” and it bothers me, because there are people like me who have anxiety (or depression) that can really impact their ability to function. I don’t think someone with anxiety or depression would feel comfortable enough to wear a shirt like that.

I was afraid people would think I was just part of a trend

I was worried people would think that I was following some bizarre trend where people use the term “anxiety attack” to describe a time where they felt stressed, or say that they have anxiety when they have no reason to seek a diagnosis.

Emphasizing “stress” may also have a downside

It’s a catch-22 though, because if we present to a college campus, “Here’s what anxiety looks like, and here’s what average stress looks like,” people who are suffering from undiagnosed disorders will worry that their symptoms aren’t real enough [to be considered anxiety], like I did. The nature of anxiety makes it hard to come out and say to someone, even a medical professional, “I don’t think that it’s normal to feel this anxious so often.”

“This was no way to experience college”

A student’s experience with generalized anxiety disorder

By Debbi*, third-year undergraduate, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania

(*Name changed)

What my anxiety looked and felt like

I’ve always been an anxious person. Being away from home, an only child very close to my parents, factored into it. My college schedule, with my course load and extracurriculars, was crazy; I left my room at 7:30 a.m. and got back at 10 p.m. I started waking up nauseous. I often didn’t sleep well because I was paranoid about missing my alarm. My morning routine became: wake up, cough so hard that it made me throw up, pretend that I was fine so that my roommate wouldn’t worry, and then go to class. During finals week I broke out in hives.

What happened when I went to counseling

When I eventually went to counseling services at the college, that helped. They’re free, and available to help us, so why not? You fill out a survey that rates how you’re feeling. Because it’s private, it’s easy to say, “My stress level is at a 9/10 right now,” and for the counselor to reassure you that it’s valid if that’s what you are feeling, and then to talk about why that is.

How I recognized I needed more help

In my case, counseling was not enough. My anxiety symptoms were still happening and I was just over it. This was no way to experience college. With my counselor’s blessing, I went to the doctor. I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety and seasonal affective disorder (depression in the winter months) and prescribed an antidepressant for the harder months of the year (November–May). I take long walks with my friends at night to settle my mind before bed. Being open about my feelings helps too. I’m doing much better now.

By Dr. Carol Lucas, director of counseling and support services at Adelphi University, New York

Anxious about whether or not to seek support with anxiety? Here’s how to know:

Early action on anxiety keeps life manageable

“Where young adults get into trouble in college is when they’ve missed a few assignments, maybe they’re failing, and they haven’t talked to anyone. And the further they get behind, the bigger the mountain they have to climb to get back to where they need to be,” says Dr. Laura Richardson, interim director of the division of adolescent medicine at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington.

Early action can prevent an anxiety disorder

“Ideally, we try to reach students before the stress rises to the level where it’s an anxiety disorder,” says Dr. Carol Lucas of Adelphi University, New York.

“For a lot of students, their way of coping with stress and anxiety is through rumination and intense worry and has been habituated for many, many years. Sometimes the work (in counseling) is helping them to think differently and find very effective practices to tolerate and manage anxiety and feelings,” says Dr. Lucas.

By Debbi*, third-year undergraduate, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania

(*Name changed)

Truly anxious people don’t make light of anxiety

The term “anxiety” is thrown around loosely. Everyone seems to “have anxiety;” it has almost become a trend. Everyone gets nervous and stressed out sometimes, but having an anxiety disorder is different. I’ve seen shirts around that say, “Stressed, depressed, but well dressed,” and it bothers me, because there are people like me who have anxiety (or depression) that can really impact their ability to function. I don’t think someone with anxiety or depression would feel comfortable enough to wear a shirt like that.

I was afraid people would think I was just part of a trend

I was worried people would think that I was following some bizarre trend where people use the term “anxiety attack” to describe a time where they felt stressed, or say that they have anxiety when they have no reason to seek a diagnosis.

Emphasizing “stress” may also have a downside

It’s a catch-22 though, because if we present to a college campus, “Here’s what anxiety looks like, and here’s what average stress looks like,” people who are suffering from undiagnosed disorders will worry that their symptoms aren’t real enough [to be considered anxiety], like I did. The nature of anxiety makes it hard to come out and say to someone, even a medical professional, “I don’t think that it’s normal to feel this anxious so often.”

Dai*, second-year undergraduate, University of California, Los Angeles

(*Name changed)

“College students face a unique stigma against reaching out to health professionals because entering college comes with the expectation that you will be stressed most of the time and that you will work late into the night. I am under the impression that all my peers are going through what I am going through, even if that isn’t actually the case.”

“I was afraid my life would crumble”

A student’s experience with specific (academic) anxiety

By Dai* second-year undergraduate, University of California, Los Angeles

(*Name changed)

What my anxiety looked and felt like

It was a lingering feeling that if I had an assignment due, I should be working on it as much as possible—that if I didn’t keep up my GPA, my life would crumble. The anxiety affected my ability to enjoy student life and my time off with friends. It was especially bad in my dorm room, so I tended to stay out late studying in the library. At times my anxiety kept me from studying; I would worry incessantly about procrastinating and how to study more. It doesn’t surprise me that anxiety is one of the most common reasons for dropping out of college. Having to juggle an academic and social life, in a new place, can be a lot more stressful than anyone can prepare for.

How I took better care of myself

It’s helpful to exercise regularly, and to focus on my extracurriculars instead of just my academics. I think of all the safety nets in my life and all the ways that I could rebound after a devastating test or quarter. For example, every time I worry about failing a test or class, I think about how I could take the next quarter off to recuperate, or how even if I had to drop out, I could still take classes at my community college and then return to four-year college.

Why I’ll seek help if it happens again

My advice to fellow students struggling with anxiety is to seek help from a health professional. I think counseling would have helped ease the burden on me and the friends on whom I relied heavily. I did not consider how taxing it could be for them to support me; they were taking my anxiety upon themselves in addition to all their own difficulties. This year, if my anxiety hinders my ability to study, I will look for someone to help me separate my anxiety about a class from my ability to study for that class.

By Dr. Carol Lucas, director of counseling and support services at Adelphi University, New York

For evidence-based strategies to manage your time, read Student Health 101.

Get the mind-soothing benefits of movement

Get regular physical activity

People who are regularly active are less prone to anxiety, according to numerous studies. “Exercise can be a powerful addition to the range of treatments for depression, anxiety, and general stress,” said Dr. Michael Otto, professor of psychology at Boston University, Massachusetts, in a report by the American Psychological Association. A single workout can help alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms, according to the ADAA. Physical activity appears to be protective against anxiety disorders (Depression and Anxiety, 2008).

How to be active when your feelings are blah

Focus more on the immediate mood-boosting benefits of physical activity and less on its long-term effects (such as weight management and warding off chronic disease). This works, because the immediate effects are more motivating. “Usually within five minutes after moderate exercise you get a mood-enhancement effect,” said Dr. Otto, who is co-author of Exercise for Mood and Anxiety: Proven Strategies for Overcoming Depression and Enhancing Well-Being (Oxford University Press, 2011).

For tools and resources, see Find out more today.

Prioritize your sleep, wellness, social support, and self-awareness

For tools and resources, see Find out more today.

Seek professional support

Anxiety disorders are usually treated with counseling, medication, or both. “Talk therapy” helps you identify your problems and figure out ways to address them. A variety of approaches can help, depending upon the problem. You and your therapist will decide which approach is best for you.

Your campus counseling center is a good place to start. Here’s how that might go:

“Students come in when anxiety completely impacts their work. We tell them that no one has ever died of feelings, but people do die trying to control or avoid them.

“In counseling, we work with students to be able to tolerate their feelings, tolerate the stress, and take a look at what your day looks like. What are some of the things you can change?

“What are your expectations? There is such a heavy emphasis on performance and on grades that we try to help them feel good about what they’re doing. Are you cramming or leaving papers until the last minute? We try to help them organize their days so that they’re not constantly slamming into this stress.”

—Dr. Carol Lucas, director of counseling and support services at Adelphi University, New York

For tools and resources, see Find out more today.

If necessary, consider medication

If counseling is not enough or you are in a state of crisis, talk with your counselor and other health care providers (such as your primary care physician) about additional resources and options.

A combination of psychotherapy and medication may produce better outcomes than either alone, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. For example, a review of 21 studies suggests that combined treatment improves outcomes for panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (World Psychiatry, 2014).

A range of medications is available to help with anxiety:

For tools and resources, see Find out more today.

Tons about mental health on campus: Active Minds

More college-specific resources: Jed Foundation

Info and resources: Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA)

Apps that help with anxiety: ADAA

Free mindful meditations: UCLA

Exercise for Mood and Anxiety: Proven Strategies for Overcoming Depression and Enhancing Well-Being: Michael Otto and Jasper Smits

(Oxford University Press, 2011)

[survey_plugin]

Article sourcesEric Goodman, PhD, clinical psychologist, Coastal Center for Anxiety Treatment, San Luis Obispo, California.

Carol Lucas, PhD., LCSW, director, counseling and support services division of Student Affairs; adjunct professor, School of Social Work, Adelphi University, New York.

Laura Richardson, MD, MPH, interim director, division of adolescent medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington.

American College Health Association. (2015, Spring). National College Health Assessment. Retrieved from https://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2015_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

Anderson, E., & Shivakumar, G. (2013). Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4(27).

Anwar, Y. (2013, June 25). Tired and edgy? Sleep deprivation boosts anticipatory anxiety. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://news.berkeley.edu/2013/06/25/anticipate-the-worst/

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2016). Generalized anxiety disorder. Retrieved from https://www.adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/generalized-anxiety-disorder-gad

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2016). Facts. Retrieved from https://www.adaa.org/finding-help/helping-others/college-students/facts

Brunes, A., Augestad, L. B., & Gudmundsdottir, S. L. (2013). Personality, physical activity, and symptoms of anxiety and depression: The HUNT study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(5), 745–756.

Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S. L., Andersson, G., et al. (2014). Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 56–67.

Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1935–1682. Retrieved from

https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/bejeap.2009.9.1/bejeap.2009.9.1.2191/bejeap.2009.9.1.2191.xml

Goldstein, A. N., Greer, S. M., Saletin, J. M., Harvey, A. G., et al. (2013). Tired and apprehensive: Anxiety amplifies the impact of sleep loss on aversive brain anticipation. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(26), 10607–10615.

Kyrouz, E. M., & Humphreys, K. (2015). Research on self-help and mutual aid support groups. PsychCentral.com. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/library/support_groups.htm

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Anxiety disorders: Definition. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Any anxiety disorder among adults. Retrieved from

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-anxiety-disorder-among-adults.shtml

Penn State. (2015). Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) Annual Report. Retrieved from https://ccmh.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/821/sites/3058/2016/01/2015_CCMH_Report_1-18-2015.pdf

Student Health 101 survey, September 2016.

Vidourek, R. A., King, K. A., Nabors, L. A., & Merianos, A. L. (2014). Students’ benefits and barriers to mental health help-seeking. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 1009–1022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4346065/

Weir, K. (2011, December). The exercise effect. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/12/exercise.aspx