What happens when you mix alcohol with common medications?

Reading Time: 8 minutes Before you imbibe, know the side effects of mixing alcohol with prescription and OTC medications.

Reading Time: 8 minutes Before you imbibe, know the side effects of mixing alcohol with prescription and OTC medications.

Reading Time: 6 minutes Thinking about having a nightcap to help you catch some extra zzz’s before the big exam? Read this article first.

Reading Time: 2 minutes A physician explains how to determine the amount of water you really need.

Reading Time: 3 minutes We all have gas. But what happens when belching, bloating, or flatulence becomes excessive? How much is too much?

Reading Time: 7 minutes How to turn down (and respond when someone turns down) a drink.

Reading Time: 6 minutes Understanding the connection between alcohol and sexual assault can help us foster stronger, more respectful communities.

Reading Time: 11 minutes Social events are an important part of the college experience. Whether you’re a host or a guest, here’s how to make your next gathering fun for everyone.

Reading Time: 10 minutes Follow these four steps if you’re with someone who drank too much, and when in doubt call 911.

—Jayden*, Portland State University, Oregon

Yes, in ways both large and small. Are there students who drink from time to time and still manage to get good value out of their investment in higher education? Of course. In fact, most students would fit this description. But alcohol can still impair your learning experience. Here are several ways that this can happen:

If you’re drinking, you aren’t in a state to concentrate or remember, meaning you aren’t learning. For many college students, drinking is part of blowing off steam and relaxing after a hard few hours of academic work. In moderation, this may not present any problems. You just have to weigh the risks and be conscientious in your decision-making. It’s certainly the case that drinking to the point of being sick or having to go to the hospital, or getting in fights or injured, will likely soak up much more time than you’ve budgeted. If you have a big paper due Monday, perhaps it would make sense to take a weekend off from drinking so you have plenty of time to complete your work at a high-quality level. I often challenge students to take two to three weeks off from drinking just to prove to themselves that they can, and to see what it’s like.

Learning has several components. You have to be concentrating when exposed to ideas, in order to form short-term memories. While you sleep, those short-term memories are consolidated into long-term memories. Research has shown a linear relationship between hours of sleep and GPA—in other words, the more you sleep, the better you do academically.

Not sleeping enough, or getting poor-quality sleep, impedes long-term memory formation and thus the learning process. Drinking often affects decision-making, leading you to stay up later than you’d planned, and the sleep that you get when intoxicated is relatively poor quality (though it’s healthier than engaging in other activities while intoxicated; e.g., driving).

There are many reasons not to drink on a particular night. Maybe you’re sick or taking medication. Maybe you have a big test the next day, or want to do well at tryout. Maybe you just don’t feel like it. At the top of the list is depression and anxiety. If you are unhappy, don’t drink. Very few things in this world are 100 percent true, but this is one of them: Drinking will worsen your experience of depression. There are much better medicines than alcohol. Ask for help at your student health center or counseling center.

Drinking amplifies most emotions. This can lead to euphoria, arousal, the belief that you’re an amazing dancer, and so on. Drinking can also lead to drama, and sometimes physical violence. It’s your life, of course. Personally, I find my life complicated enough without alcohol ramping things up.

Getting in trouble for underage possession, intoxication, vandalism, or anything else does not provide any short-term benefit to your educational experience.

For some students, the stakes are much higher than getting a B instead of the A- you were capable of. About 10–15 percent of people are at particularly high risk for addiction. Their brains are wired in such a way that they struggle to control their relationship with alcohol and/or other substances. Unless they get help, and that help is effective, they are at high risk for suffering serious consequences, such as damaged relationships, financial difficulties, and the inability to complete their schooling on schedule. Sometimes it takes a serious consequence, like failing out of school, to help them come to terms with their condition. But ideally the problem would be identified and rectified before the consequences became profound.

(*Name changed)

Do you choose to drink alcohol? If so, chances are you’re interested in figuring out how to get alcohol’s buzz (feeling chatty, relaxed, and socially connected) while avoiding its negative effects (feeling tired, sick, embarrassed, and all set to fail Monday’s test).

You may have noticed that once you’ve passed the euphoric stage of drinking, and started to slump, consuming more alcohol does not bring back the buzz. This is always the case (science has figured out why, but that’s another story).

This guide is about how to get the effects of alcohol that you want without ending up with its baggage too. A key skill is knowing how to take care of yourself while still being part of the party. Here, we outline seven realistic ways to do this.

Note: Our emphasis is on realistic. Most of you are using some of these strategies already, a large national survey shows. To find out how to make this easier, while expanding your options for having fun and staying in control, keep reading. These strategies are especially important when you’re new to college, new to drinking, or both. (The minimum legal age for consuming alcohol in the US is 21.)

Alcohol seems (and is) part of the social culture on many campuses. But over and over, studies show that students perceive alcohol use among their peers to be far more common and frequent than it really is. Here’s what undergrads think their peers are drinking, compared to how much undergrads report they are actually drinking:

Here’s what undergrads think their peers are drinking, compared to how much undergrads report they are actually drinking: Source: National College Health Assessment, Fall 2015; 19,800 respondents, anonymous and randomized

Source: National College Health Assessment, Fall 2015; 19,800 respondents, anonymous and randomized

Planning what you’ll drink through the evening is key to staying in control.  Consider:

Consider:

To figure out what works for you, see Know what you can drink—at what pace later in this slideshow.

Part of planning is anticipating whether you will have control over your own alcohol choices. For example, if jungle juice or mystery punch is all that’s available, the healthiest choice is not to drink or to bring your own.

Let your friends know that you’re looking forward to hanging out with them and that you’re choosing to not overdo it. Can’t afford a late penalty for your assignment or a missed team practice? Your friends will get it.

You’re not the only one who wants to be in control when you go out. Tag team with a friend, help each other out, and celebrate the people who step in and let you know when you’ve had enough.

We feel more comfortable when we have a cup in our hand, whether or not that cup contains alcohol, studies show.

Good to know: Studies of the placebo effects related to alcohol show that the chatty, witty persona we associate with drinking is more about our expectations of alcohol than the alcohol itself. In other words, we can be that person without alcohol.

You can delay your next drink without seeming to reject the person who’s offering it or distancing yourself from the social scene.

When someone offers to get you a drink, show appreciation, and give them a reason to hold off.

Bonus: This sets you up to get your own drink directly from the bartender—the safest source of alcohol. Here’s why:

The person offering you a drink wants you to have a good time and include you in the fun. Let them see that you’re enjoying yourself.

Drinking games vary in their safety and risk. If you participate, choose wisely.

Be cautious about matching your alcohol intake with someone else’s. When participating in drinking games, we often consume more than we had anticipated, and we drink more quickly than usual. This hikes up the risk of illness, impairment, and regret. Consider adapting drinking games in these ways:

Consider adapting drinking games in these ways:

Those strategies are helpful in social and professional situations involving alcohol. Being mindful about your alcohol use also means knowing what you typically drink and how your body and mind respond to it. Here’s how to figure that out:

How to calculate your alcohol intake (Rethinking Drinking: NIAAA)

This helps you estimate the amount of drink servings you can consume, and how you should pace them, before your Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) reaches “peak buzz”. For many people, “peak buzz” is around 0.06 percent BAC. For some, it’s between 0.04 and 0.06.

Predict how you’ll feel through the evening (Yale University)

Estimate your BAC during dinner (Éduc’alcool)

Almost all college students (98 percent) who responded to a national survey reported that they routinely took one or more smart measures when socializing with alcohol in the past 12 months.

| “Most of the time” or “always” | |

| Alternate non-alcoholic with alcoholic beverages | 35 percent |

| Avoid drinking games | 37 percent |

| Choose not to drink alcohol | 26 percent |

| Decide in advance not to exceed a set number of drinks | 43 percent |

| Eat before and/or during drinking | 80 percent |

| Have a friend let you know when you have had enough | 44 percent |

| Keep track of how many drinks being consumed | 68 percent |

| Pace drinks to one or fewer an hour | 34 percent |

| Stay with the same friends the entire time drinking | 88 percent |

| Stick with only one kind of alcohol when drinking | 52 percent |

| Use a designated driver | 89 percent |

Source: National College Health Assessment, Fall 2015; 19,800 respondents, anonymous and randomized

Effective tools and tips for having fun and staying in control

Rethinking Drinking: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Handle your urge to drink and friends who offer: NIAAA

Facts, tips, and tools for young adults: Éduc’alcool

Calculators for alcohol content, calories, cost, etc.: NIAAA

Guides to the social dynamics around drinking alcohol: BestCollegeReviews.org

Jason Kilmer, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, University of Washington; assistant director of health and wellness for alcohol and other drug education, Division of Student Life, University of Washington.

Joan Masters, MEd, senior coordinator, Partners in Prevention, University of Missouri Wellness Resource Center; area consultant, The BACCHUS Network.

Ann Quinn-Zobeck, PhD, former senior director of initiatives and training, The BACCHUS Network.

Ryan Travia, MEd, associate dean of students for wellness, Babson College, Massachusetts; founding director, Office of Alcohol & Other Drug Services (AODS), Harvard University.

American College Health Association. American College Health

Association–National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group

Undergraduates Executive Summary Fall 2015. Hanover, MD: American

College Health Association; 2016.

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13, 391–424. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.602.7429&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2006). How the quality of peer relationships influences students’ alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25(4), 361–370.

Crawford, L. A., & Novak, K. B. (2007). Resisting peer pressure: Characteristics associated with other-self discrepancies in college students’ levels of alcohol consumption. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 51(1), 35–62.

Harrington, N. G. (1997). Strategies used by college students to persuade peers to drink. Southern Communication Journal, 62(3), 229–242. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10417949709373057?journalCode=rsjc20

Kilmer, J., Cronce, J. M., & Logan, D. E. (2014). “Seems I’m not alone at being alone:” Contributing factors and interventions for drinking games in the college setting. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(5), 411–414.

Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., et al. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 556–565.

Neighbors, C., Jensen, M., Tidwell, J., Walter, T., et al. (2011). Social-norms interventions for light and nondrinking students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 651-669. doi: 10.1177/1368430210398014

Palmeri, J. M. (2016). Peer pressure and alcohol use among college students. Applied Psychology Opus, NYU Steinhardt. Retrieved from

https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/appsych/opus/issues/2011/fall/peer

Perkins, H. W., Linkenbach, J. W., Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2010). Effectiveness of social norms media marketing in reducing drinking and driving: A statewide campaign. Addictive Behaviors, 35(10), 866–874.

Roberts, C., & Robinson, S. P. (2007). Alcohol concentration and carbonation of drinks: The effect on blood alcohol levels. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 14(7), 398–405.

Rohsenow, D.J., & Marlatt, G. A. (1981). The balanced placebo design: Methodological considerations. Addictive Behaviors, 6(2), 107–122. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(81)90003-4

Student Health 101 survey, July 2016.

Turner, J., Perkins, H. W., & Bauerle, J. (2008). Declining negative consequences related to alcohol misuse among students exposed to social norms marketing intervention on a college campus. Journal of American College Health, 57, 85−93.

Wechsler, H., Nelson, T. E., Lee, J. E., Seibring, M., et al. (2003). Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 484–494.

If you choose to drink alcohol, you’re likely familiar with the relaxed, chatty buzz that may come early in the evening—and the slump that sometimes follows (the tiredness, the nausea, maybe the fear of what you posted online). If you’re drinking in school, you can learn how to get that buzz without the slump. For those who drink alcohol, this skill is key to a night—no, a lifetime—of positive experiences and few, if any, regrets.

What makes alcohol tricky to navigate? First, we need to understand how alcohol affects us—which in certain key respects is different from popular myth. With those basic concepts, we can choose to drink alcohol in ways that give us what we want from it.

Second, we all like to believe that we make our own choices, and to some extent, we do. But it’s complicated. A ton of research shows that our behavior, including what we drink, is highly dependent on what’s happening around us. In college, getting the alcohol buzz without the slump means grappling smartly with social dynamics, in addition to understanding the science of how alcohol affects us. This is especially relevant when you’re new to college, new to drinking, or both. (The minimum legal age for consuming alcohol in the US is 21.)

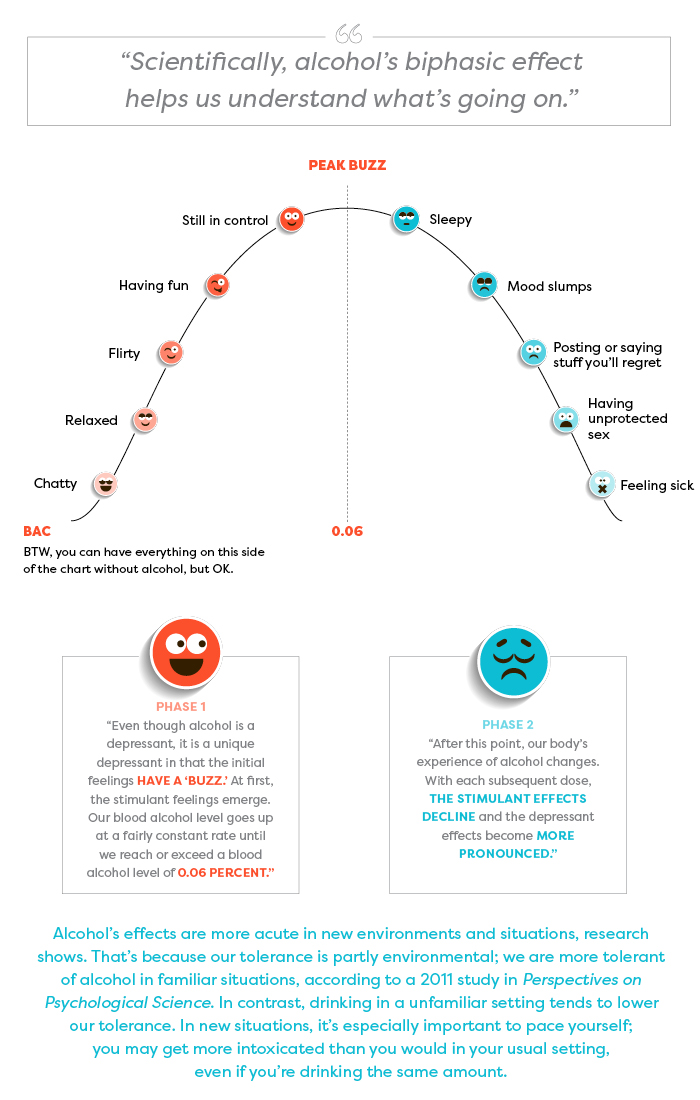

If you choose to drink alcohol, it may help you relax, socialize, and have fun—up to a point. Depending on what you drink, how much you drink, and how quickly or slowly you drink it, the alcohol level in your blood will rise to a certain level—let’s call it “peak buzz.”

For most people of average tolerance, peak buzz happens when your Blood Alcohol Content (BAC)—the concentration of alcohol in your bloodstream—approaches 0.06 percent. For most people, two to three drinks within an hour will have this effect. Some research indicates that 0.06 percent BAC is on the high side; you may find peak buzz comes at any point after 0.04 BAC.

Beyond that point—0.06 percent BAC—the enjoyable effects of alcohol decline and wear off. You may feel sleepy, flat, disconnected. You may get moody or sick, or make unwise decisions. From here, there’s no going back to peak buzz. Drinking more alcohol can only take you deeper into the slump and toward regret territory.

Explained by Dr. Jason Kilmer, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, University of Washington:

“The biphasic aspect actually occurs within the brain. The brain center that inhibits our actions is the first to be affected (depressed) by alcohol. So without the inhibiting center the other areas somewhat go wild, and we feel uninhibited, etc. Later, the brain functions that allow us to act bolder and less shy also get depressed, and then we slump.” —Dr. Pierre-Paul Tellier, director of student health services at McGill University, Quebec

These buzz effects and slump effects in the chart are examples of how people may experience alcohol; the sequence of effects on each side of the chart is in no particular order.

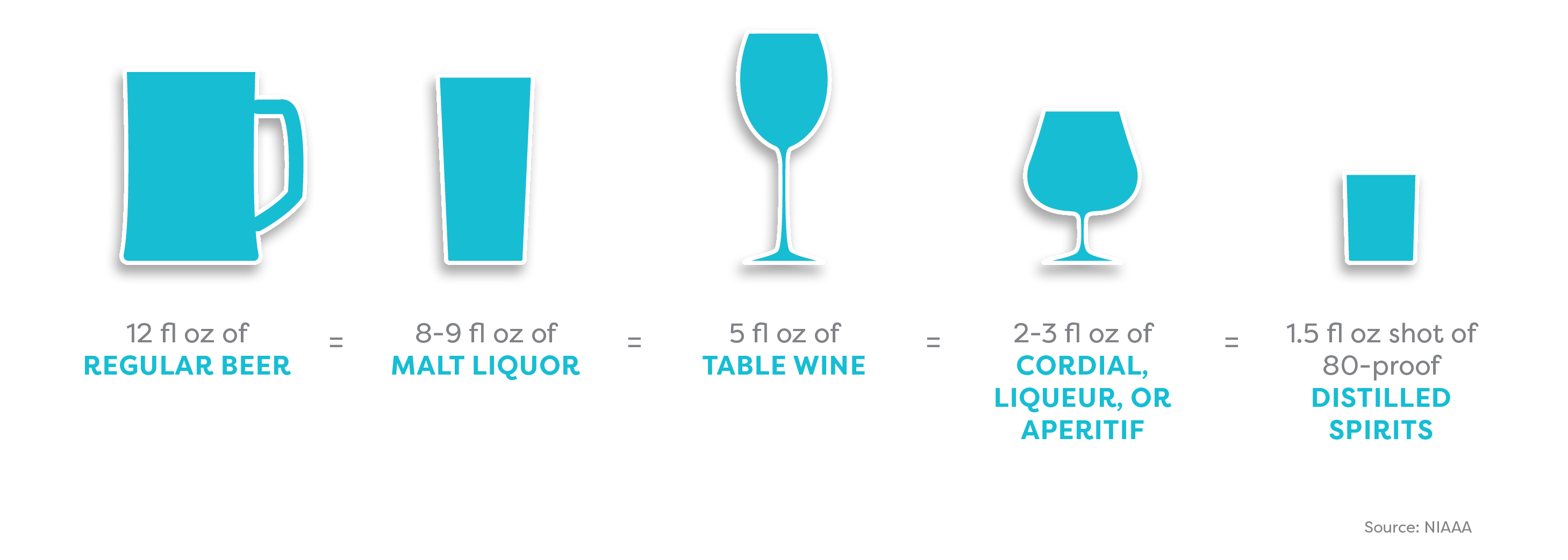

The amount of alcohol you consume depends partly on what you’re drinking. Alcoholic beverages vary enormously in their alcohol content.

The amount of alcohol you consume also depends on the shape and size of your glass or cup. A standard serving size is unlikely to be whatever your new friend just ladled into that solo cup.

How to get the hang of serving sizes:

Try this size calculator (NIAAA)

The same size beverage can look very different depending on the size and shape of the cup or glass.

Think about pacing your drinking. Most people take about one hour to metabolize one standard drink. If you’ll be out for, say, four hours, and you plan to have three alcoholic drinks, you may decide to have one alcoholic drink per hour for the first three hours.

Pregaming—drinking before you go out—means you hit peak buzz earlier. If you keep drinking, your mood declines earlier too.

BAC calculators and charts help you estimate the number of standard drinks you can consume before your BAC reaches peak buzz (0.06 percent).

Example:

Woman (155 lb, 5’7″): 3 standard drinks in 3 hours

Man (155 lb, 5’7″): 3 ½ standard drinks in 3 hours

Check out this BAC chart (Yale University)

Or this one (Cleveland Clinic)

BAC charts and calculators are useful but limited tools:

They do not account for various other factors that may influence your alcohol tolerance (e.g., age, health, fatigue, medications, food consumed, and whether or not the environment is familiar).

You may need to adjust the BAC percentage to account for the amount of time you’re drinking.

Effective tools and tips for having fun and staying in control

Rethinking Drinking (info, tools, etc.): National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Handle your urge to drink and friends who offer: NIAAA

Calculators for alcohol content, calories, cost, etc.: NIAAA

Guides to the social dynamics around drinking alcohol: BestCollegeReviews.org

Stopping at the buzz: GoodTherapy.org

Best alcohol apps of 2016: Healthline.com

Article sources

Jason Kilmer, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, University of Washington; assistant director of health and wellness for alcohol and other drug education, Division of Student Life, University of Washington.

Joan Masters, MEd, senior coordinator, Partners in Prevention, University of Missouri Wellness Resource Center; area consultant, The BACCHUS Network.

Ann Quinn-Zobeck, PhD, former senior director of BACCHUS initiatives and training, NASPA - Student Affairs Professionals in Higher Education (peer education initiatives addressing collegiate health issues at US colleges).

Pierre-Paul Tellier, MD, director of student health services, McGill University, Quebec.

Ryan Travia, MEd, associate dean of students for wellness, Babson College, Massachusetts; founding director, Office of Alcohol & Other Drug Services (AODS), Harvard University.

American College Health Association. American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Undergraduates Executive Summary Fall 2015. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2016.

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13, 391–424. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.602.7429&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2006). How the quality of peer relationships influences students’ alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25(4), 361–370.

Crawford, L. A., & Novak, K. B. (2007). Resisting peer pressure: Characteristics associated with other-self discrepancies in college students’ levels of alcohol consumption. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 51(1), 35–62.

Harrington, N. G. (1997). Strategies used by college students to persuade peers to drink. Southern Communication Journal, 62(3), 229–242. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10417949709373057?journalCode=rsjc20

Kilmer, J., Cronce, J. M., & Logan, D. E. (2014). “Seems I’m not alone at being alone:” Contributing factors and interventions for drinking games in the college setting. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(5), 411–414.

Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 556–565.

Neighbors, C., Jensen, M., Tidwell, J., Walter, T., Fossos, N., & Lewis, M. A. (2011). Social-norms interventions for light and nondrinking students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 651-669. doi: 10.1177/1368430210398014

Palmeri, J. M. (2016). Peer pressure and alcohol use among college students. Applied Psychology Opus, NYU Steinhardt. Retrieved from https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/appsych/opus/issues/2011/fall/peer

Perkins, H. W., Linkenbach, J. W., Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2010). Effectiveness of social norms media marketing in reducing drinking and driving: A statewide campaign. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 866–874.

Seigel, S. (2011). The four-loko effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 357–362.

Student Health 101 survey, July 2016.

Turner, J., Perkins, H.W., & Bauerle, J. (2008). Declining negative consequences related to alcohol misuse among students exposed to social norms marketing intervention on a college campus. Journal of American College Health, 57, 85−93.

Wechsler, H., Nelson, T. E., Lee, J. E., Seibring, M., Lewis, C., & Keeling, R. P. (2003). Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 484–494.

Rate this article and enter to win

Going to a party? Or throwing one? Party-throwers and party-goers play a vital role in shaping the sexual culture of your campus. Party-throwers are the social engineers who design the spaces in which students meet, dance, talk, and sometimes drink or hook up. A well-planned environment helps everyone to make mindful decisions. And as a party guest, you can do a lot to make this easier for your host and more fun for yourself and others. Every time you demonstrate mutual respect, you reduce the likelihood of campus sexual assault and/or alcohol poisoning. Here’s how to throw a great party and be a great guest.

The minimum legal age for consuming alcohol in the US is 21.

Set the tone

How you talk about a party can go a long way in helping your guests imagine what it will be like. What’s the tone or vibe you want for your party? For example:

Set expectations

Are there “house rules” you want your guests to know about? For example:

Set a friendly tone

Consider explicitly assigning someone (or a few people) the task of greeting guests and inviting them in.

House rules

If there’s stuff your guests need to know, like when this thing is shutting down, consider posting it in the entryway.

Check in with arriving guests

Are they arriving alone? Slurring their words? Wobbly on their feet? You might want to check in with someone’s friends, get them medical attention, or not serve them any more alcohol.

Send people home safely

Make sure your guests have a safe way to get home. Check in with them as they leave. Post info about taxi and ride services, as well as medical response resources in case of accidents or alcohol poisoning.

Here’s why that works out better for you:

Check in with your neighbors

Check in with your campus security department

Check campus policies and state laws

Not everyone has fun the same way all the time.

Dance space

When you’re putting together the playlist or choosing entertainers or DJs, think about how well they fit your values and priorities for the party. Avoid music that seems derogatory or aggressive.

Chill space

Provide a quieter, more well-lit space where your guests can hang out, catch their breath, and talk. Play softer music. It’s a good idea to stock this space with cold water bottles and low-salt, high-protein snacks.

A set-up that makes room for conversation will help your guests communicate more clearly. This is especially important if two people are considering going home together.

Think about adding activities (apart from dancing) that don’t involve alcohol, like Jenga®, board games, and trivia.

If there are isolated spaces in your party venue, decide whether or not to keep them open and accessible.

If not: Lock the door, rope off the space, and/or hang signs saying the space is closed.

If you keep isolated areas open, assign someone the task of checking in on those spaces throughout the party.

Get medical help in case of alcohol poisoning

Take a moment to familiarize yourself with the medical response resources available on your campus or in your community. If everything goes according to plan, your guests will drink safely and won’t need to use them.

Any of the following symptoms indicates alcohol poisoning

Call for medical help immediately:

Handle difficult guests

Keep your cool. Controlling tone and body language can be tricky, but it’s crucial to prevent the situation from escalating further.

Make yourself noticeable

Pick a certain color, a silly hat, or a large pin (“Here to help!”). This lets guests know where to turn if anything comes up. If a large group is throwing the party, consider trading off “hosting duties” through the evening.

Model supportive social dynamics

Party-throwers are especially attuned to the general mood. You get to take the lead on looking out for one another and treating guests with respect. If you drink alcohol, stop after one or two.

Make the rounds

Introduce people and troubleshoot issues as they come up.

Check isolated spaces, such as bedrooms, closets, and yards.

Subtly disrupt uncomfortable situations

Maybe a guest is getting unwanted attention or someone is pressuring others to drink. It’s your party: You can check in whenever you notice something, no matter how small. The most effective interventions happen early and subtly. Distract people, change the topic, make a joke or an introduction.

If you plan to serve alcohol, aim for an environment in which everyone can make mindful, deliberate choices about whether they want to drink and how much. A successful party does not have to involve alcohol.

If you serve alcohol:

For guests, this set up makes drinking an active choice rather than a default. It’s easier for people to count their drinks over the course of the evening.

Designated servers are awesome at these party skills:

Many campuses and community organizations offer classes on bartending skills and safe serving practices—often for free.

Notice the tone

The invitation (whatever form it takes) should give you some idea of what your hosts have in mind. Big house party? Chill get-together?

Respect their house rules

Validate the hosts’ trust in you. They might want to keep certain areas off-limits, or they may need to end things at a certain hour.

Plan ahead

Think about what you want out of the party. If alcohol will be served: Do you want to drink? How much? You can have a great time at any party without drinking any alcohol. If you do plan to drink, a good rule of thumb is one standard drink every hour or 1½ hours.

Be a good sport about the theme

If your hosts have gone through the trouble of coming up with a theme, do your best to play along. A good theme will make room for everyone to participate in whatever way they feel comfortable, so feel free to find your own.

Get in touch with your host at least a day in advance. Do they need help setting up? Or staying late to help clean up? This a great way to show your appreciation.

If you want to bring something, consider snacks (preferably low-salt and high-protein ones, like Greek yogurt dip or hummus with veggies) or mixers. These go quickly at parties, and your hosts will appreciate having extras.

Find the host when you arrive

You’re here to see them, and they’ll be happy to know you made it. Ask if they could use a hand with anything.

If you don’t know many people there, tell your host

They want you to have fun. They probably have a good sense of who you’ll get along with, and can introduce you.

If you see new faces in the room, say hello

Offer to show them around, and introduce them to other guests. You’ve been that newbie—remember the relief when someone made you feel welcome in a new space.

If you’re the newbie, branch out

Fun means different things to different people. Some people would rather hang out and talk than spend the night on the dance floor. Some people will be more comfortable getting physical than others. Whatever it is, pay attention to the cues you’re getting, and respect them.

If you notice a troubling dynamic, think about how best to step in

Perhaps you notice someone experiencing unwanted attention or being pressured to drink more than they want to. Maybe you see some broken glass or someone in need of medical attention.

Whatever it is, there’s always something you can do

This is your community, and you play an important role in making it a positive and supportive one. You could:

If you’re worried that your friend is pressuring others

This can be a great opportunity for a stealthy intervention—for example, by joining a conversation or people on the dance floor. If you’re close to your friend, you can always demand that they consult you about something important in the other room.

People have different limits when it comes to alcohol

Many people make the decision not to drink alcohol at all. Pressuring someone to drink beyond their limit puts them at risk and creates more work for your host. That guest who drinks too much may get sick, need medical attention, or be unable to get home safely.

Trust your own limits

Be especially cautious if you are stressed or sleep-deprived, taking medication, have alcohol misuse in your family, or have diabetes. If you’ve chosen to drink alcohol, remember to pace yourself so that you’re sober enough to enjoy the party and the company of your friends. Tips for drinking safely:

Include people who don’t want to drink

Thank the host for a great party

Ask if they need anything before you head out: Can you lend a hand cleaning up? Can you walk someone home or give them a ride?

Don’t leave your host in the lurch

If your host is dealing with drunk or unruly guests, ask what you can do to help. Maybe you could suggest that everyone head out for pizza, help find the stragglers’ friends, or offer them a ride home.

Thank your host

They’ll be happy to hear what you enjoyed. If their party planning supported different ways to have fun, say how much you appreciated it.

Check in with anyone you may have been concerned about at the party

How to party smart: Harvard Drug and Alcohol Peer Advisors

Skills for safe alcohol consumption: TIPS®

What you can do to help: Who Are You?

Find local services for sexual assault survivors: NotAlone.gov

Get active against sexual assault: Know Your IX

Bystander tips and training: University of Arizona (Step UP! Program)

Melanie Boyd, PhD, assistant dean in student affairs at Yale University; lecturer in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies.

Abbey, A. (2011). Alcohol’s role in sexual violence perpetration: Theoretical explanations, existing evidence, and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(5), 481–489.

Abbey, A. (2002). Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students [Supplement]. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 14, 118–128.

Benson, B. J., Gohm, C. L., & Gross, A. M. (2007). College women and sexual assault: The role of sex-related alcohol expectancies. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 341–351.

Banyard, V. L., Plante, E. G., & Moynihan, M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention.

Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1), 61–79.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., & Eliseo-Arras, R. K. (2008). The making of unwanted sex: Gendered and neoliberal norms in college women’s unwanted sexual experiences.

Journal of Sex Research, 45(4), 386–397.

Carmody, M. (2005). Ethical erotics: Reconceptualizing anti-rape education. Sexualities, 8(4), 465–480.

Hingson, R. W. & Howland, J. (2002). Comprehensive community interventions to promote health: Implications for college-age drinking problems.

Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement 14, 226–240.

Lindgren, K. P., Pantalone, D. W., Lewis, M. A., & George, W. H. (2009). College students’ perceptions about alcohol and consensual sexual behavior: Alcohol leads to sex.

Journal of Drug Education, 39(1), 1–21.

Mohler-Kuo, M., Dowdall, G. W., Koss, M. P., & Wechsler, H. (2004). Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women.

Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 65(1), 37–45.

Sweeney, B. N. (2011). The allure of the freshman girl: Peers, partying, and the sexual assault of first-year college women. Journal of College & Character, 12(4).