Talk it out: The science behind therapy and how it can help you

New class expectations, new living situations, and navigating newfound independence can give us all the feels—from super psyched to super stressed. Even if you’re loving your student life, dealing with all the stressors that come with college can be a lot to handle. According to experts, the best time to handle that stress is now. “If we don’t take care of our mental health, we may not be able to reach our goals, maintain good relationships, and function well in day-to-day situations,” says Dr. Chrissy Salley, a psychologist in New York who works with students of all ages. “Taking care of mental health is one of the best things someone can do.”

Now really is the time to start tuning into your mental health—the majority of mental health issues appear to begin between the ages of 14 and 24, according to a review of the World Health Organization World Mental Health surveys and other research (Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 2007). But help is available. Along with methods like mindfulness and meditation, talking to a therapist (such as a counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist) can be a super-effective way to manage any mental health issue you may be facing or just a way to get extra support during times of stress, challenge, celebration, or change.

There’s a ton of research on how effective therapy really is—a 2015 meta-analysis of 15 studies of college students with depression found that outcomes were nearly 90 percent better for those who received therapeutic treatment than for those in control groups, most of whom received no treatment (Depression and Anxiety).

One of the most common and effective therapies is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a short-term, goal-oriented therapy where a pro helps you find practical ways to deal with specific problems.

OK, so we know that therapy is an essential and effective tool for keeping your mental health at its peak, but making that first appointment can feel intimidating. It doesn’t have to be. Our experts break down the therapy basics so you can embrace whatever you need to feel your best. Here’s what the pros want you to know.

Surveys show it’s not out of the ordinary to see a therapist—55 percent of college students have used campus counseling services, according to a 2012 report from the National Alliance on Mental Illness. If you feel uncomfortable with the idea of going to see a therapist, you’re not alone—and that’s totally OK, says Zachary Alti, a licensed social worker, psychotherapist, and professor at the Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service in New York. “Few people look forward to therapy, but students should be aware that therapy exists to help them, not to judge them,” he says. The process might not always be comfortable, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth it. “I’d encourage students to keep an open mind and try it,” says Dr. Salley.

“Many [young people] tell me they’re reluctant to participate in therapy because they don’t want to talk about their feelings,” Dr. Salley says. Again, that’s totally normal. But going to therapy isn’t just about talking about how you feel; it’s also about walking away with real tools you can use in your life. “Therapy should also be action oriented—a time to learn new skills for coping and figuring out ways to solve problems,” Dr. Salley says.

“Therapy is like physical exercise,” says Alti. Just like hitting the gym is good for everyone’s physical health—not just those with diabetes or heart disease—seeing a therapist can benefit everyone’s mental health.

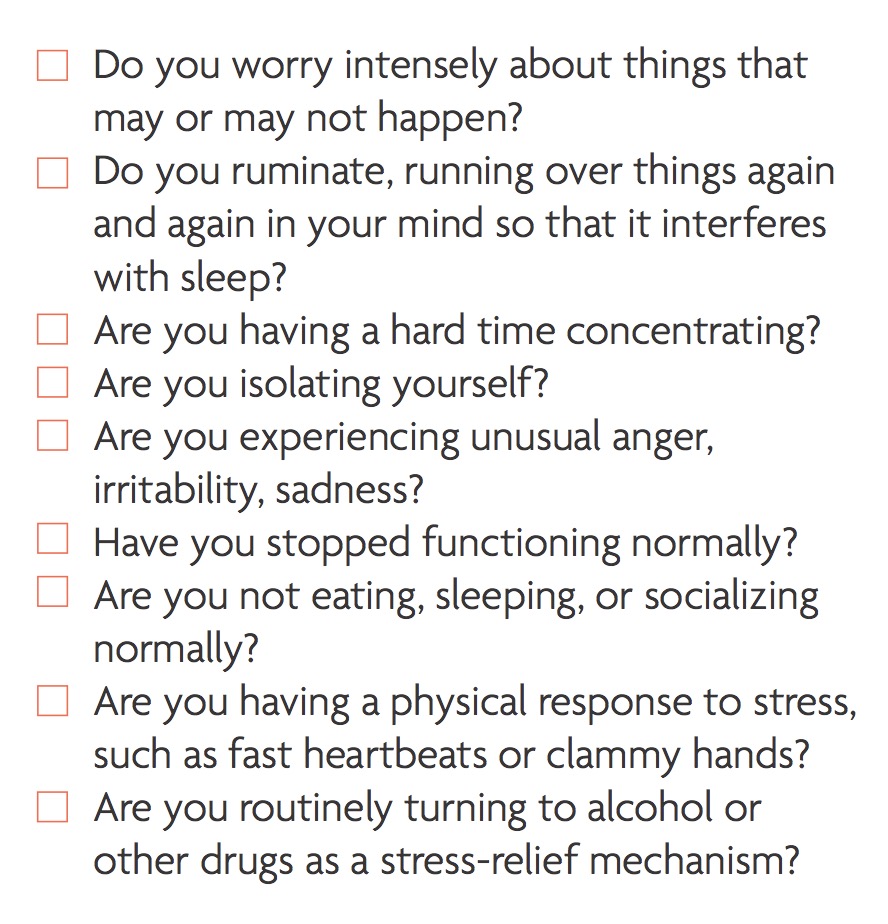

But really, any time is a good time to go. While anxiety and depression are still the most common reasons students seek counseling, according to a 2016 annual report from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health, you don’t have to be in the midst of a crisis or feel like you’re nearing a breakdown to see a pro—seeing a therapist can be helpful even when things are all good. “There are a lot of pink flags before you get to red ones,” says Dr. Dana Crawford, an individual and family therapist in New York. “Keeping things from becoming extreme is always better.” In other words, don’t wait for an emergency to take care of your mental health. “When bad things do happen, mental health will protect against the impact of these unfortunate events,” adds Alti.

Student perspective

“Being able to just have someone to really listen has promoted a lot of self-discovery. I trust my therapist with everything and I feel like he genuinely cares about what I have to say. He asks me questions that make me think about why I feel and do the things that I do. Once I know where something comes from, I can change it. It’s easier said than done, but it’s not something I think I could do on my own.”

—Second-year undergraduate student, University of Alabama[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Real talk: College is full of huge life changes. “Even positive changes can be stressful,” says Dr. Salley. Luckily, therapists are particularly skilled at helping their clients deal with these transitions. “Having someone to talk to can be helpful, especially as you encounter new situations and people,” she says. While you’re dealing with a new set of responsibilities and expectations (everything from picking the right major to sorting through awkward roommate issues), a therapist can help you pinpoint how all the changes are impacting you and sort through the onslaught of emotions that everyone feels during this time.

Therapists aren’t one-size-fits-all—sometimes you have to try a few before you find the right fit. Don’t get turned off if your first therapy appointment isn’t super helpful—if something feels uncomfortable, listen to your gut, but don’t give up, says Dr. Crawford. “You would never go to the store, try on a pair of jeans, and say, ‘Oh, those don’t fit, I guess I won’t wear jeans.’ You would keep trying jeans until you found the right fit,” says Dr. Crawford. Same goes for therapists.

Finding that fit with a therapist is just as important for the outcome as the actual therapeutic technique, according to findings presented in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work (Oxford University Press, 2004). The research analysis found that three key things had a measurable positive impact on the outcome of individual therapy: 1) the strength of your collaborative relationship with your therapist—aka are you on the same page and making goals for your treatment together?; 2) your therapist’s ability to empathize or see where you’re coming from; and 3) the degree to which you and your therapist outline goals and reevaluate them together.

In other words, to get the most out of a therapy session, take the time to find someone you feel like you’re on the same page with, who gets you, and who’s willing to listen to your goals for therapy and help you develop them.[/vc_column_text][vc_tta_accordion shape=”square” c_icon=”chevron” active_section=”0″ collapsible_all=”true”][vc_tta_section title=”Ask these questions to help you find the right fit” tab_id=”1509035547084-fd2f65e1-167e”][vc_column_text]

- What types of therapy are you trained in?

- What issues do you specialize in?

- What populations do you specialize in? (While all therapists take on different types of clients, some specialize in specific groups such as working with LGBTQ+ people, people of color, or those who’ve been marginalized in some way.)

- How do you invite all aspects of your client into the room? (It’s important to know how your therapist will address all aspects of your culture, says Dr. Crawford. “You want to know that you can talk to your therapist about all parts of who you are.”)

- What are your beliefs about how people change?

- What’s your goal for ending therapy? (Some therapists believe therapy is an ongoing thing that you never really graduate from, while others see it as a tool to resolve a specific challenge. Make sure their goals line up with yours, and if not, ask if you can redefine them together.)

Check with your insurance provider to see whether you need a referral to see a psychologist or counselor. If so, you may need to make an appointment with your primary care provider or the student counseling center to ask for one. Once you have the referral (if needed), you can seek out a therapist in a number of ways:

- Ask friends and family members if they have a therapist they recommend.

- Find out if your school counseling center has a list of recommended providers.

- Use the American Psychological Association’s online search tool.

- Call your insurance company or use their online services to find a list of therapists who are covered by your plan. If you get a personal recommendation from someone, you’ll also need to check that they’re covered under your insurance plan.

Once you have a name or a list of names and you’ve checked that the providers are covered by your insurance plan, call each therapist and leave a message to ask if they’re accepting new patients and to call you back with their available hours. When you hear back from the therapist, you may want to discuss what you’re looking to get out of treatment, what days and times you’re available to meet, and what their fees are—confirm that they take your insurance (it never hurts to double check this)—and ask about their training and make sure they’re licensed. Sometimes it can take a few tries to find someone whose schedule works with yours, but don’t let that deter you.[/vc_column_text][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion][vc_column_text]

“Therapy can be useful by helping people acquire a better understanding of themselves and develop healthy habits,” says Dr. Salley. For example, if you have trouble getting up in time to make that optional early-morning lecture, but then you beat yourself up about missing it, a therapist can help you identify what you really value and then help you make decisions based on that. “It can be helpful to talk to someone who’s objective and not a friend to bounce your experiences and feelings off of,” says Dr. Crawford. “A therapist’s only investment is for you to be your best self.”

Once you’ve identified what’s really important to you, a therapist can help give you the tools to make your value-driven goals a reality. “Problems that are unaddressed remain problems,” says Dr. Crawford. “When you’re ready for something different in your life, it can change. Therapy can help you create the future you want.”

You may be worried that all that talking might get out or that your therapist might tell your advisor or RA about what you’re struggling with. “A therapist isn’t allowed to do this unless the student poses a threat to themselves or others,” says Alti. “A therapist’s effectiveness is dependent on maintaining trust.” Bottom line: Unless they believe you’re in imminent danger (e.g., at risk of being seriously harmed or harming yourself or others), they can’t share what you say.

In short, everyone can benefit from talking to a therapist. “In the same way that everyone can benefit from going to the dentist, sometimes therapy is just a routine cleaning,” says Dr. Crawford. “Sometimes it’s just a time to reflect on where you are and where you want to go.” Whether you’re wrestling with anxiety and depression or mildly stressed about finding a summer internship, seeing a therapist can help—even if it’s just for a few sessions. (According to the CCMH report, the average student who uses campus psychology services attends between four and five sessions.)

Student perspective

“Therapy was a good way to talk through anything weighing on my mind. My therapist was very understanding, kind, and, of course, confidential. I’d recommend going to counseling services to everyone.”

—Third-year undergraduate student, Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[school_resource sh101resources=’no’ category=’mobileapp,counselingservices’] Get help or find out more

Find a therapist: American Psychological Association

A sample script for contacting a therapist: UC Davis

Your online resource for college mental health: ULifeline

Learn more about types of therapy: American Psychological Association

What you need to know before choosing online therapy: American Psychological Association

Zachary Alti, LMSW, clinical professor, Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service; psychotherapist in New York City.

Dana Crawford, PhD, individual and family therapist, New York.

Chrissy Salley, PhD, pediatric psychologist, New York.

American Psychological Association. (2017). How to find help through seeing a psychologist. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/therapy.aspx

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Protecting your privacy: Understanding confidentiality. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/confidentiality.aspx

APA Practice Organization. (2017). Psychologist locator. Retrieved from https://locator.apa.org/

Brown, H. (2013, March 25). Looking for evidence that therapy works. New York Times. Retrieved from https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/25/looking-for-evidence-that-therapy-works/

Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2017, January). 2016 Annual Report. (Publication No. STA 17-74). Retrieved from https://sites.psu.edu/ccmh/files/2017/01/2016-Annual-Report-FINAL_2016_01_09-1gc2hj6.pdf

Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Ebert, D. D., Koot, H. M., et al. (2016). Psychological treatment of depression in college students: A meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 33(5), 400–414. doi: 10.1002/da.22461

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., et al. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J. et al. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

Martin, B. (2016, May 17). In-depth: Cognitive behavioral therapy. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/lib/in-depth-cognitive-behavioral-therapy/

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2012). College students speak: A survey report on mental health. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Survey-Reports/College-Students-Speak_A-Survey-Report-on-Mental-H.pdf

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Mental health facts: Children and teens. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/getattachment/Learn-More/Mental-Health-by-the-Numbers/childrenmhfacts.pdf

Norcross, J. C., & Hill, C. E. (2004). Empirically supported therapy relationships. Psychotherapy Relationships That Work, 57(3), 19–23.

UC Davis. (n.d.). Community referrals. Retrieved from https://shcs.ucdavis.edu/services/community-referrals