What does an opioid overdose look like? Learn the signs and where to get help

Reading Time: 6 minutes By now, many of us probably know someone who’s been affected by opioid addiction. Learn how to spot the signs of an overdose and where to get help.

Reading Time: 6 minutes By now, many of us probably know someone who’s been affected by opioid addiction. Learn how to spot the signs of an overdose and where to get help.

Reading Time: 9 minutes Giving your body time to recover between workouts can actually be more beneficial than going hard seven days a week. Learn how to incorporate so-called “active rest” into your training routine to maximize your gains.

Rate this article and enter to win

Stretching: It’s an important part of any fitness routine, research shows. Obvs, you might think. But really, it’s important to take stretching (before and after a workout) seriously. Stretching is what helps your muscles stay flexible and strong and keeps the range of motion in your joints moving the way it should. Ditch stretching and you risk tighter and weaker muscles, Harvard researchers say, which can not only be uncomfortable, but make you less able to use your muscles to the best of your ability (e.g., losing an intense arm wrestling challenge in front of all your friends—womp).

Below, our experts take you through three types of stretching: dynamic (before your workout), static (after your workout), and an advanced sequence for serious fitness buffs.

Warming-up sets the foundation for an effective, safe workout by preparing the body for exercise and reducing the risk of injury. Dynamic stretching involves controlled, full-range movement. When done correctly, it can improve flexibility, lubricate the joints, and prepare the nervous system by telling the body it’s time to move.

Used to stretch muscles when the body is at rest, static stretching focuses on flexibility and increases your range of motion. It also helps muscle relax and lengthen, which is why it’s best done after your workout.

These stretches are most beneficial to those who regularly engage in intense physical activities such as running, cycling, or plyometrics, and help increase your range of motion for common exercises, relaxation, and can correct any imbalances in muscle movement. Perform these stretches intuitively (meaning the length of time on each stretch depends on how your body responds to the stretch) and in any order, as many times as you like.

Keep in mind that when stretching, you might feel mild discomfort. Take deep breaths to fully experience the stretch. If you have sharp pain, decrease the depth of the stretch. If the pain persists, make an appointment to meet with a personal trainer or health care provider.

Warming up is essential regardless of your exercise experience and physical ability. Personal trainer Frankie takes you through three upper-body stretches and three lower-body stretches to prep your body for your workout.

Personal trainer Eliza helps you stretch out each muscle (including chest, tricep, groin, and hamstring) post sweat sesh with these static stretches, to help the body recover post workout. Hold each for 30–60 seconds.

These stretches will help increase the range of motion in your joints, allowing you to get the most out of your workout—especially if you’re an athlete or person in training. Florence leads you through stretches of your hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstring, the piriformis muscle, toes, feet, and calves.

[survey_plugin]

Rate this article and enter to win

Most of us have supported friends through difficult times, such as a break-up, academic pressure, or family issues. But how do we step up and provide support when friends and loved ones experience sexual assault and other forms of sexual violence? Especially when the person who experienced the assault is male?

Social pressure and stereotypes about gender can make it particularly challenging for men who’ve been assaulted to talk about their experiences. If one of your male friends or loved ones is assaulted, it’s important that you know you’re in a position to help.

Many of the challenges men face reflect social pressure: ideas that sexual assault makes them less masculine, that women can’t assault men, or that “real men” don’t talk about or get help for painful experiences. “Some men fear that they’ll be seen as less of a man,” says Dr. Jim Hopper, a researcher, therapist, and instructor at Harvard Medical School. “If they’re heterosexual, they may fear people will doubt their sexuality. And if they’re gay or bisexual, they may blame the assault on their sexuality in a way that further stigmatizes their being gay or bisexual.”

A common belief is that sexual violence only affects women. In fact, many men have unwanted sexual experiences, as both children and adults. One in six men in the US is sexually assaulted before age 18, according to studies from the 1980s to the early 2000s. In 2015, seven percent of men reported being sexually assaulted while attending college, according to a study by the Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation. Regardless of the targeted man’s sexual orientation, both men and women perpetrate these assaults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013).

“Sex, gender identity, and race can all influence how an experience like this affects someone, but it’s very important you have no presumption about what it feels like to your friend—so listen,” says Dr. Melanie Boyd, assistant dean of student affairs and lecturer in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Yale University in Connecticut.

Everyone is different. People’s varying personalities and circumstances affect how they respond to an unwanted sexual experience and what we can do to help. For example, some people want lots of hugs, while some prefer verbal support. The most important thing is to relate to your friend in a way that can help him feel empowered and connected. As a friend, you’re in a great position to do this.

When a friend discloses an experience of violence, it’s normal to feel a wide range of emotions, such as shock, confusion, sadness, or anger. In the moment, keep the conversation focused on your friend’s emotions, not your own.

“Many people who experience sexual violence also experience some degree of self-blame,” says Dr. Boyd. “Partially, that’s just what people do when something bad happens: We go over the events in our head, hunting for things we could have done differently. It’s a way of regaining a sense of control. In the case of sexual violence, though, survivors also have to contend with victim-blaming patterns that run through our culture. So it’s important that friends help them push back against that. Be careful not to say or ask anything that might suggest blame—and affirm for your friend that he did the best he could in a difficult, complicated situation.”

As challenging an experience as a sexual assault may be, it’s not as though your friend has become an entirely different person. The “othering” of people who’ve been assaulted—treating them differently—can be just as dangerous as ignoring or minimizing unwanted sexual experiences, according to researchers Nicola Gavey and Johanna Schmidt (Violence Against Women, 2011). Avoid thinking of the assault as something that cuts your friend off from the rest of the world; in fact, it’s up to you to be supportive and counteract that.

Make sure to listen and focus on your friend’s feelings. “Pay attention to their specific issues,” says Dr. Boyd.

Avoid pronouns that assume the gender of the perpetrator or that make other assumptions about the experience. “I think one of the most important issues is breaking down the stereotype that only women are abused,” said Lena*, a second-year undergraduate at Tarrant County College in Texas.

“As a friend, you want to relate to them in a way that gives them power, including by giving them choices and respecting whatever choices they make on whatever timeline,” says Dr. Hopper.

“Supporting someone through the healing process can be stressful, hard, and exhausting. That’s why it’s important for supports to take of themselves,” says Bella Alarcon, a bilingual clinician at the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center who facilitates a support group for partners, friends, and family of people who’ve experienced sexual violence. Paying attention to your own needs isn’t selfish. “If you’re exhausted and overwhelmed, you’re not going to be able to support the survivor,” says Alarcon.

Be mindful of your own needs, and make sure that you’re getting support.

*Names changed

Strategies developed by the Communication and Consent Educator program at Yale University.

[school_resource sh101resources=’no’ category=’mobileapp,titleix, counselingservices, suicideprevention, titleix’] Get help or find out moreHow to support a male friend: 1in6

Helpline and many other resources: RAINN

Resources for survivors: Living Well

Help for survivors: National Sexual Assault Hotline and Online Hotline

LGBTQ hotline and meet-up groups: Trevor Project

Information and resources for LGBTQ survivors of violence: Anti-Violence Project

Men share their stories of dealing with sexual violence: The Bristlecone Project

Bella Alarcon, bilingual clinician, Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, Massachusetts.

Melanie Boyd, PhD, assistant dean in student affairs; lecturer in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, Yale University, Connecticut.

Jim Hopper, PhD, independent consultant and clinical instructor in psychology, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts.

1in6. (n.d.). Sorting it out for himself. Retrieved from https://1in6.org/family-and-friends/sorting-it-out-for-himself/

Abelson, M. J. (2014). Dangerous privilege: Trans men, masculinities, and changing perceptions of safety. Sociological Forum, 29(3), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12103

Anderson, N., & Clement, S. (2015, June 12). Poll shows that 20 percent of women are sexually assaulted in college. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/local/2015/06/12/1-in-5-women-say-they-were-violated/

Anderson, S. S., Hendrix, S., Anderson, N., & Brown, E. (2015, June 12). Male survivors of sex assaults often fear they won’t be taken seriously. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/male-victims-often-fear-they-wont-be-taken-seriously/2015/06/12/e780794a-f8fe-11e4-9030-b4732caefe81_story.html

Beres, M. A. (2014). Rethinking the concept of consent for anti-sexual violence activism and education. Feminism & Psychology, 24(3), 373–389.

Beres, M. A., Herold, E., & Maitland, S. B. (2004). Sexual consent behaviors in same-sex relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(5), 475–486.

Brenner, A. (2013). Transforming campus culture to prevent rape: The possibility and promise of restorative justice as a response to campus sexual violence. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender. Retrieved from https://harvardjlg.com/2013/10/transforming-campus-culture-to-prevent-rape-the-possibility-and-promise-of-restorative-justice-as-a-response-to-campus-sexual-violence/

Carmody, M. (2003). Sexual ethics and violence prevention. Social & Legal Studies, 12(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663903012002003

Catalano, S. (2013). Intimate partner violence: Attributes of victimization, 1993–2011. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4801

Colorado State University. (n.d.). A Guide for supporting survivors of sexual assault. Retreived from https://wgac.colostate.edu/supporting-survivors

Crome, S. (2006). Male survivors of sexual assault and rape. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/publications/male-survivors-sexual-assault-and-rape

Crome, S. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Adult rape scripting within a victimological perspective. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(4), 395–413.

Davies, M., Gilston, J., & Rogers, P. (2012). Examining the relationship between male rape myth acceptance, female rape myth acceptance, victim blame, homophobia, gender roles, and ambivalent sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(14), 2807–2823.

Davies, M., & Rogers, P. (2006). Perceptions of male victims in depicted sexual assaults: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(4), 367–377.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Brown, D. W., et al. (2005). Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5), 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015

Gavey, N., & Schmidt, J. (2011). “Trauma of rape” discourse: A double-edged template for everyday understandings of the impact of rape? Violence Against Women, 17(4), 433–456.

Gavey, N., Schmidt, J., Braun, V., Fenaughty, J., et al. (2009). Unsafe, unwanted: Sexual coercion as a barrier to safer sex among men who have sex with men. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(7), 1021–1026.

Graham, R. (2006). Male rape and the careful construction of the male victim. Social & Legal Studies, 15(2), 187–208.

Grand Rapids Community College. (n.d). Step-by-step. Retrieved from

https://www.grcc.edu/studentaffairs/sexualmisconduct/stepbystep

Harrell, M. C., Castaneda, L. W., Adelson, M., Gaillot, S., et al. (2009). A compendium of sexual assault research. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR617.pdf

Hopper, J. W. (2015, June 23). Why many rape victims don’t fight or yell. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2015/06/23/why-many-rape-victims-dont-fight-or-yell/

Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade: Clinical implications and management. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 263–287.

Maine Coalition Against Sexual Violence. (n.d.). Sexual violence against LGBTQQI populations. Retrieved from https://www.mecasa.org/index.php/special-projects/lgbtqqi

Masters, N. T. (2010). “My strength is not for hurting”: Men’s anti-rape websites and their construction of masculinity and male sexuality. Sexualities, 13(1), 33–46.

Monk-Turner, E., & Light, D. (2010). Male sexual assault and rape: Who seeks counseling? Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 22(3), 255–265.

Paulk, L. (2014, April 30). Sexual assault in the LGBT community. National Center for Lesbian Rights. Retrieved from https://www.nclrights.org/sexual-assault-in-the-lgbt-community/

RAND Office of Media Relations. (n.d.). Complete results from major survey of US military sexual assault, harassment released. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/news/press/2015/05/01.html

Rothman, E. F., Exner, D., & Baughman, A. L. (2011). The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 12(2), 55–66.

Sleath, E., & Bull, R. (2010). Male rape victim and perpetrator blaming. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(6), 969–988.

Stanko, E. A., & Hobdell, K. (1993). Assault on men: Masculinity and male victimization. British Journal of Criminology, 33(3), 400–415.

Strauss, V. (2014, August 29). Does “restorative justice” in campus sexual assault cases make sense? Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/08/29/does-restorative-justice-in-campus-sexual-assault-cases-make-sense/

Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Breiding, M. J. (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf

Weiss, K. G. (2010). Male sexual victimization examining men’s experiences of rape and sexual assault. Men and Masculinities, 12(3), 275–298.

Willis, D. G. (2009). Male-on-male rape of an adult man: A case review and implications for interventions. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(6), 454–461.

Rate this article and enter to win

What if students have gone through treatment for alcohol addiction or drug abuse, and now they’re back on track, focusing on their education and future? Their success in school depends on managing their sobriety. But college comes with stress, academic challenges, and exposure to alcohol or drugs—factors that can raise the risk of relapsing, studies show. Increasingly, substance dependency (or addiction) is understood as a chronic condition that requires ongoing management. For sober students, this is the dilemma: How can they steer clear of those triggers and manage their addiction while also having a fulfilling college experience?

Increasingly, students who are “in recovery”—working to maintain their sobriety—are finding the solution in dedicated recovery programs on campuses. These programs vary, but may include drug-free housing, sober hangout space, social events with supportive peers, and meetings, counseling, and academic supports tailored to address the pressures and triggers associated with staying free of alcohol and/or drugs.

Increasingly, students who are “in recovery”—working to maintain their sobriety—are finding the solution in dedicated recovery programs on campuses. These programs vary, but may include drug-free housing, sober hangout space, social events with supportive peers, and meetings, counseling, and academic supports tailored to address the pressures and triggers associated with staying free of alcohol and/or drugs.

More than 170 university campuses now offer some level of recovery programming, according to Transforming Youth Recovery, a nonprofit that provides schools with funding and other resources for this purpose. The organization has a pilot project underway to expand capacity for recovery services at 100 community colleges.

“People are starting to know there is recovery support on college campuses and are looking around for it,” says John Ruyak, an alcohol, drug, and recovery specialist at Oregon State University. In a 2016 study involving nearly 500 students at 29 campus recovery programs, one in three said they would not be in college were it not for that program (Journal of American College Health).

Shifting medical and societal attitudes toward addiction appear to be helping. “There’s a trend to recognize dependency/addiction as a chronic illness, like diabetes or Crohn’s disease,” says Dr. Davis Smith, a staff physician at the University of Connecticut Student Health Center, and medical director of Student Health 101. “Like those physical conditions, substance dependency behaves differently in different individuals, is not a marker of physical or spiritual weakness, and requires ongoing attention/treatment to manage it.”

This increasingly empathic understanding of drug dependency makes it easier for people to seek the resources that could help them. “Students have changed enough that they are not so worried about anonymity as they are about finding the support,” says Dr. Ann Quinn-Zobeck, former senior director of BACCHUS initiatives and training at NASPA (Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education), a leader in peer-education initiatives addressing alcohol use at US colleges.

It also helps that students in recovery are not the only ones who are avoiding alcohol and drugs. “The data on student alcohol and other drug use makes it clear that while many students do use at some level, more and more are abstaining for a variety of reasons,” says Dr. Beth DeRicco, director of higher education outreach for Caron Treatment Centers, who has extensive experience developing policies and programs that address dangerous drinking and drug use on campuses and in our broader communities. Among more than 29,000 US students who responded to a national, anonymous survey, 20 percent reported that they had never drunk alcohol, and 16 percent said they had drunk alcohol but not in the past 30 days (National College Health Assessment, spring 2016).

Early research suggests that these programs can help students succeed academically and graduate from college. A 2014 study involving 29 collegiate recovery communities found that their students had higher GPAs and graduation rates than the general student populations at the same colleges (Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions).

That success reflects the determination of these students to move forward, says Joan Masters, senior coordinator at Partners in Prevention, a consortium addressing substance abuse on Missouri campuses. “Students in recovery take every choice seriously and day-by-day. Going back into higher education is a commitment, their second chance.” The relapse rates of students in these programs appears to be well below those of adults accessing community-based recovery services, according to the same 2014 study.

Recovery supports work better when they are designed to meet the needs associated with specific life stages and environments, research shows (SAMHSA, 2009). “For most students in recovery, collegiate recovery programs provide the social support and peer network critical to maintaining recovery,” says Dr. DeRicco.

The key components of campus programs may be peer-based groups, 12-step recovery supports, and academic supports, according to a 2011 study in Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. College administrations are well positioned to facilitate these.

Part of the solution is as simple as physical infrastructure. “Universities can help facilitate students getting together and supporting themselves and each other; having dedicated space makes that easier,” says Ruyak. Early class registration means students don’t have to choose between accessing recovery supports and meeting their academic requirements, he says. “Students need to put their recovery first. If you don’t, it’s hard to be the best student you can be.”

Collegiate recovery communities vary widely, both in the types of services available and in what they require of the students who access them. “There are many models of different types,” says Masters. “In Missouri, we allow each college to pick what works for them while maintaining fidelity to various tenets of recovery.”

Campus recovery programs typically include some (but not necessarily all) of the following elements:

Programs may specify a particular recovery approach or allow students to choose what works for them. For example, at Oregon State University, “We want students to choose their path of recovery. We don’t define what that looks like as long as it is positive for the community and they are not using,” says Ruyak.

The average age of students in college recovery programs is 26, according to the Journal of American College Health (2016)—a number that hints at the nontraditional routes of many students in recovery (as explained below). “In our program, they’re from age 19 into their 40s, ranging from people who are literally just getting sober to people with nine years of sobriety,” says Sarah Nerad, program manager of the collegiate recovery community at The Ohio State University.

The campus recovery population may include:

Many recovery communities are open to others, including:

If you’re already in college, ask about recovery services at your disability services office, counseling center, or student health center. If you’re not in school or are considering a transfer, check college websites and/or contact their student health centers. The membership requirements for recovery programs are variable. “There are many campus programs and policies that support substance-free living, and students in recovery benefit from these as does the general population of students,” says Dr. DeRicco. “If you have taken time out for substance use treatment and are looking to return to school, factors that improve your chance of success include the presence of a campus recovery program, psychoeducational programming (e.g., handling stress and triggers), and access to group meetings.”

Some elements of programming (e.g., sober housing and early class registration) may be restricted to students who meet specific membership requirements. Other elements (e.g., sober meeting space and social events) may be open to students who are not members of the recovery program but can benefit from those resources and/or support students in recovery.

To be admitted to recovery programming, staff may consider:

The program may require:

Supportive peers are highly valuable to recovery. If you are new to recovery and want to start a group on campus, reach out to other students who have more experience. “When you have a year or two of recovery under your belt, a leadership role comes more naturally,” says Nerad.

What if starting a campus-based group is not an option?

This may be an issue on small campuses where there are not enough students in recovery to maintain an ongoing group. “You can find a lot of the same benefits in traditional models of recovery. There are 12-step meetings and counseling opportunities everywhere, and those can work as a starting point to build the fellowship that comes out of a campus org,” says a fourth-year undergraduate member of a campus recovery program at a midwestern university.

It’s not necessarily easy to know if your own alcohol and/or drug use has become problematic. If alcohol and/or drugs are negatively affecting your life, or you’re having trouble moderating your use, it’s important to seek help earlier rather than later. “People in their late 20s, 30s, and 40s say, ‘I wish I’d got sober in college’,” says Nerad. Under diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), addiction or dependency (termed substance use disorder), can be mild, moderate, severe, or in remission.

Six percent of the US student population meets the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependency, according to the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs (2002). For some students, risk-taking is a developmental stage that they outgrow. Others may be self-medicating in response to an underlying emotional and/or physical health issue that isn’t being addressed in healthier ways.

When students seek help managing their alcohol or drug use, it’s usually in response to an alarming experience. “They woke up one day and realized their situation was not good; they got black-out drunk, they need help,” says Nerad. “They go to the student health center, counseling center, or health educator. Some students look up AA.” Many colleges have online screening tools for identifying risky substance use and assessing the need for further support, and brief interventions that can help students manage their use and avoid further negative consequences.

These questions can help you figure out if your drinking or drug use is problematic:

11 criteria that indicate problematic use (VeryWell.com)

Treatment for alcohol and/or drug misuse can take a variety of forms

“Depending on the level of care needed, a young person may or may not need to take a medical leave from campus,” says Dr. DeRicco. She outlines these treatment options:

How to find recovery tools, resources, and community

A bridge to recovery on campus: New York Times

Info and resources for students: Association of Recovery In Higher Education (ARHE)

Success stats on campus recovery: Oregon State University

Toolkits for starting a recovery program: Transforming Youth Recovery

Find or start a local chapter: Young People in Recovery

Self-management recovery skills: SMART Recovery

Info and support: Alcoholics Anonymous

Info and support: Narcotics Anonymous

Beth DeRicco, PhD, director, higher education outreach, Caron Treatment Centers, Pennsylvania.

Joan Masters, MEd, senior coordinator, Partners in Prevention, University of Missouri Wellness Resource Center; regional consultant, The BACCHUS Network, NASPA.

Sarah Nerad, MPA; program manager, Collegiate Recovery Community; director of recovery, Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Drug Misuse Prevention and Recovery, Office of Student Life, Ohio State University.

Ann Quinn-Zobeck, PhD, former senior director of initiatives and training, The BACCHUS Network, NASPA.

John Ruyak, MPH, alcohol, drug, and recovery specialist, Oregon State University.

Davis Smith, MD, staff physician, University of Connecticut Student Health Center; medical director, Student Health 101.

American College Health Association. (2016, Spring). American College Health Association—National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA) reference group data report. Retrieved from https://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II%20SPRING%202016%20US%20REFERENCE%20GROUP%20DATA%20REPORT.pdf

Association of Recovery in Higher Education. (2016). The collegiate recovery movement: A history. Retrieved from https://collegiaterecovery.org/the-collegiate-recovery-movement-a-history/

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2006). How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25(4), 361–370.

Bugbee, B. A., Caldeira, K. M., Soong, A. M., Vincent, K. B., et al. (2016, August.) Collegiate recovery programs: A win-win proposition for students and colleges.

University of Maryland School of Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.cls.umd.edu/docs/CRP.pdf

Clapp, J. D. (2014, February 28). [Review of the book Substance Abuse Recovery in College: Community Supported Abstinence, by H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris, & R. Wiebe (Eds)]. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(1), 113–114.

Harrington, C. H., Harris, K. S., Baker, A. K., Herbert, R., et al. (2007). Characteristics of a collegiate recovery community: Maintaining recovery in an abstinence-hostile environment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(1), 13–23.

Harrington, C. H., Harris, K. S., & Wiebe, R.P. eds. (2010). Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence. Advancing responsible adolescent development. New York: Springer, 2010.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., et al. (2015). National survey results on drug use 1975–2015: College students and adults ages 19–55. Monitoring the Future/National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved from https://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2015.pdf

Kilmer, J. R., & Logan, D. E. (2012). Applying harm reduction strategies on college campuses. In C. Correia, J. Murphy, and N. Barnett (Eds.) College student alcohol abuse: A guide to assessment, intervention, and prevention. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Knight, J. R., Wechsler, H., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., et al. (2002). Alcohol abuse and dependence among US college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 63(3), 263.

Laitman, L., Kachur-Karavites, B., & Stewart, L. P. (2014). Building, engaging, and sustaining a continuum of care from harm reduction to recovery support: The Rutgers Alcohol and Other Drug Assistance Program. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions , 14(1), 64–83.

Laudet, A., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C. et al. (2016). In college and in recovery: Reasons for joining a collegiate recovery program. Journal of American College Health, 64(3), 238–246.

Laudet, A., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., et al. (2014). Recovery community programs: What do we know and what do we need to know? Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(1), 84–100.

Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., et al. (2015). Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs: A national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 51, 38–46.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005). A pocket guide for alcohol screening and brief intervention. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/PocketGuide/pocket.pdf

Quinn-Zobeck, A. (2007). Screening and brief intervention tool kit for college and university campuses. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration/BACCHUS Network.

Retrieved from https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/sbirt/NHTSA_SBIRT_for_Colleges_and_Universities.pdf

Smock, S. A., Baker, A., Harris, K. S., & D’Sauza, C. (2011). The role of social support in collegiate recovery communities: A review of the literature. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(1), 35–44.

Student Health 101 survey, December 2016.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2009). Designing a recovery-oriented care model for adolescents and transition age youth with substance use or co-occurring mental health disorders. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2009). Treatment episode data set (TEDS) highlights—2007: National admissions to substance abuse treatment services. SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies: Rockville, MD.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). Medication assisted treatment. Retrieved from

https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/mat/mat-overview

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Substance use disorders. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-use

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Treatments for substance use disorders. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/treatment/substance-use-disorders

Transforming Youth Recovery. (2017). Areas of focus. Retrieved from https://www.transformingyouthrecovery.org/focus

White, W., & Finch, A. (2006). The recovery school movement: Its history and future. Counselor, 7(2), 54–57.

If you choose to drink alcohol, you’re likely familiar with the relaxed, chatty buzz that may come early in the evening—and the slump that sometimes follows (the tiredness, the nausea, maybe the fear of what you posted online). If you’re drinking in school, you can learn how to get that buzz without the slump. For those who drink alcohol, this skill is key to a night—no, a lifetime—of positive experiences and few, if any, regrets.

What makes alcohol tricky to navigate? First, we need to understand how alcohol affects us—which in certain key respects is different from popular myth. With those basic concepts, we can choose to drink alcohol in ways that give us what we want from it.

Second, we all like to believe that we make our own choices, and to some extent, we do. But it’s complicated. A ton of research shows that our behavior, including what we drink, is highly dependent on what’s happening around us. In college, getting the alcohol buzz without the slump means grappling smartly with social dynamics, in addition to understanding the science of how alcohol affects us. This is especially relevant when you’re new to college, new to drinking, or both. (The minimum legal age for consuming alcohol in the US is 21.)

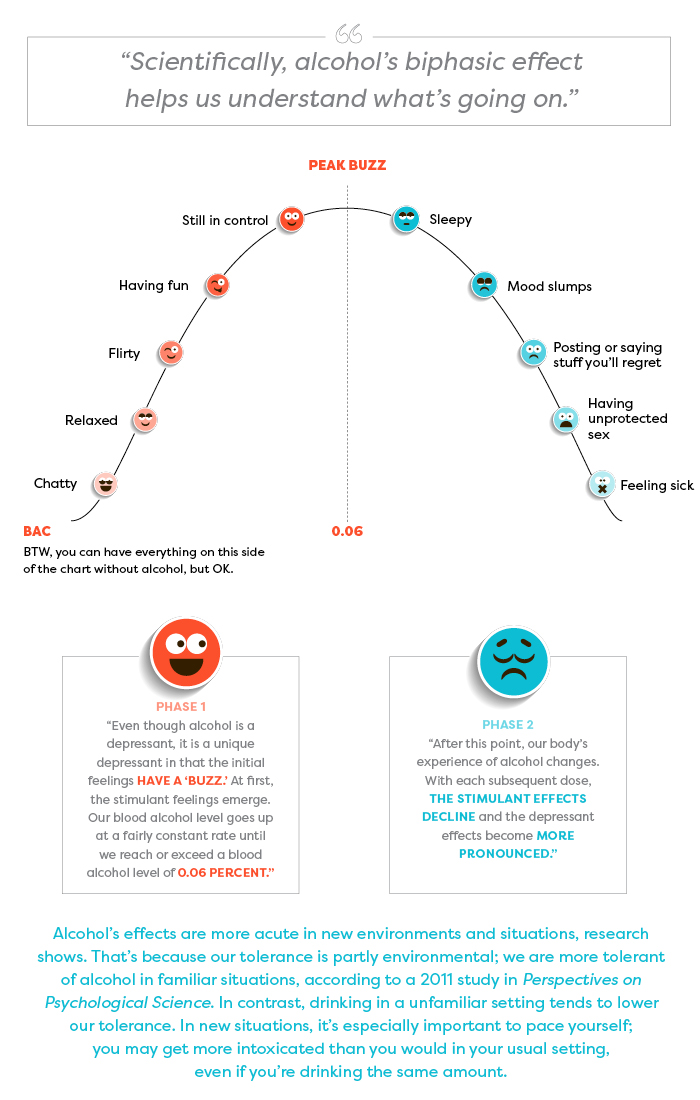

If you choose to drink alcohol, it may help you relax, socialize, and have fun—up to a point. Depending on what you drink, how much you drink, and how quickly or slowly you drink it, the alcohol level in your blood will rise to a certain level—let’s call it “peak buzz.”

For most people of average tolerance, peak buzz happens when your Blood Alcohol Content (BAC)—the concentration of alcohol in your bloodstream—approaches 0.06 percent. For most people, two to three drinks within an hour will have this effect. Some research indicates that 0.06 percent BAC is on the high side; you may find peak buzz comes at any point after 0.04 BAC.

Beyond that point—0.06 percent BAC—the enjoyable effects of alcohol decline and wear off. You may feel sleepy, flat, disconnected. You may get moody or sick, or make unwise decisions. From here, there’s no going back to peak buzz. Drinking more alcohol can only take you deeper into the slump and toward regret territory.

Explained by Dr. Jason Kilmer, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, University of Washington:

“The biphasic aspect actually occurs within the brain. The brain center that inhibits our actions is the first to be affected (depressed) by alcohol. So without the inhibiting center the other areas somewhat go wild, and we feel uninhibited, etc. Later, the brain functions that allow us to act bolder and less shy also get depressed, and then we slump.” —Dr. Pierre-Paul Tellier, director of student health services at McGill University, Quebec

These buzz effects and slump effects in the chart are examples of how people may experience alcohol; the sequence of effects on each side of the chart is in no particular order.

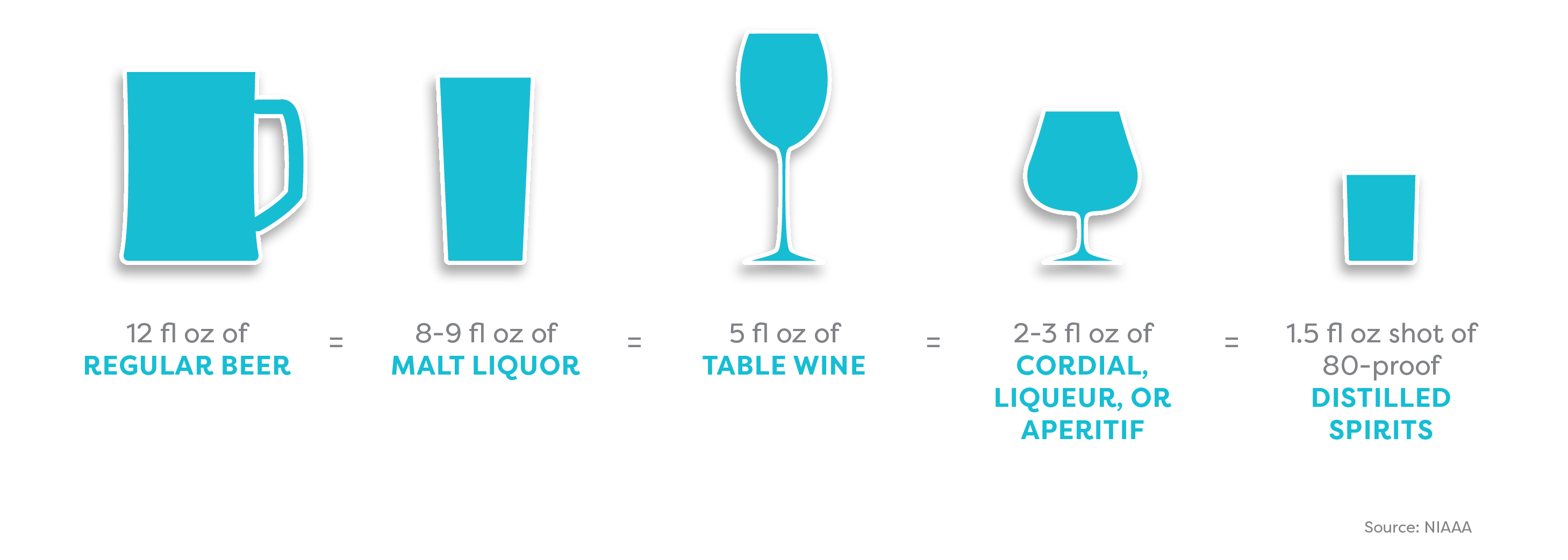

The amount of alcohol you consume depends partly on what you’re drinking. Alcoholic beverages vary enormously in their alcohol content.

The amount of alcohol you consume also depends on the shape and size of your glass or cup. A standard serving size is unlikely to be whatever your new friend just ladled into that solo cup.

How to get the hang of serving sizes:

Try this size calculator (NIAAA)

The same size beverage can look very different depending on the size and shape of the cup or glass.

Think about pacing your drinking. Most people take about one hour to metabolize one standard drink. If you’ll be out for, say, four hours, and you plan to have three alcoholic drinks, you may decide to have one alcoholic drink per hour for the first three hours.

Pregaming—drinking before you go out—means you hit peak buzz earlier. If you keep drinking, your mood declines earlier too.

BAC calculators and charts help you estimate the number of standard drinks you can consume before your BAC reaches peak buzz (0.06 percent).

Example:

Woman (155 lb, 5’7″): 3 standard drinks in 3 hours

Man (155 lb, 5’7″): 3 ½ standard drinks in 3 hours

Check out this BAC chart (Yale University)

Or this one (Cleveland Clinic)

BAC charts and calculators are useful but limited tools:

They do not account for various other factors that may influence your alcohol tolerance (e.g., age, health, fatigue, medications, food consumed, and whether or not the environment is familiar).

You may need to adjust the BAC percentage to account for the amount of time you’re drinking.

Effective tools and tips for having fun and staying in control

Rethinking Drinking (info, tools, etc.): National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Handle your urge to drink and friends who offer: NIAAA

Calculators for alcohol content, calories, cost, etc.: NIAAA

Guides to the social dynamics around drinking alcohol: BestCollegeReviews.org

Stopping at the buzz: GoodTherapy.org

Best alcohol apps of 2016: Healthline.com

Article sources

Jason Kilmer, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, University of Washington; assistant director of health and wellness for alcohol and other drug education, Division of Student Life, University of Washington.

Joan Masters, MEd, senior coordinator, Partners in Prevention, University of Missouri Wellness Resource Center; area consultant, The BACCHUS Network.

Ann Quinn-Zobeck, PhD, former senior director of BACCHUS initiatives and training, NASPA - Student Affairs Professionals in Higher Education (peer education initiatives addressing collegiate health issues at US colleges).

Pierre-Paul Tellier, MD, director of student health services, McGill University, Quebec.

Ryan Travia, MEd, associate dean of students for wellness, Babson College, Massachusetts; founding director, Office of Alcohol & Other Drug Services (AODS), Harvard University.

American College Health Association. American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Undergraduates Executive Summary Fall 2015. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2016.

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13, 391–424. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.602.7429&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2006). How the quality of peer relationships influences students’ alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25(4), 361–370.

Crawford, L. A., & Novak, K. B. (2007). Resisting peer pressure: Characteristics associated with other-self discrepancies in college students’ levels of alcohol consumption. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 51(1), 35–62.

Harrington, N. G. (1997). Strategies used by college students to persuade peers to drink. Southern Communication Journal, 62(3), 229–242. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10417949709373057?journalCode=rsjc20

Kilmer, J., Cronce, J. M., & Logan, D. E. (2014). “Seems I’m not alone at being alone:” Contributing factors and interventions for drinking games in the college setting. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(5), 411–414.

Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 556–565.

Neighbors, C., Jensen, M., Tidwell, J., Walter, T., Fossos, N., & Lewis, M. A. (2011). Social-norms interventions for light and nondrinking students. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 651-669. doi: 10.1177/1368430210398014

Palmeri, J. M. (2016). Peer pressure and alcohol use among college students. Applied Psychology Opus, NYU Steinhardt. Retrieved from https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/appsych/opus/issues/2011/fall/peer

Perkins, H. W., Linkenbach, J. W., Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2010). Effectiveness of social norms media marketing in reducing drinking and driving: A statewide campaign. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 866–874.

Seigel, S. (2011). The four-loko effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 357–362.

Student Health 101 survey, July 2016.

Turner, J., Perkins, H.W., & Bauerle, J. (2008). Declining negative consequences related to alcohol misuse among students exposed to social norms marketing intervention on a college campus. Journal of American College Health, 57, 85−93.

Wechsler, H., Nelson, T. E., Lee, J. E., Seibring, M., Lewis, C., & Keeling, R. P. (2003). Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 484–494.